As is now well-established, in 2005 the government entered indirect negotiations with the PKK command at Kandil in northern Iraq and with imprisoned PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan at Imrali. Three years later, those negotiations eventually became direct talks held in Oslo during which the government also began to pay more attention to Kurdish cultural rights within a unified Turkey. A Kurdish-language television channel, albeit government-run and largely apolitical, was introduced in the lead up to local elections in 2009, and later that summer the government announced grand plans for comprehensive reform (its “Kurdish opening,” which was later to be referred to as a “ democratic opening” ). Thus began an intense debate of what politicians, opinion leaders, and even the military began to approach as the “Kurdish problem”—not simply a problem with the PKK, but a more fundamental dilemma in demand of political solutions.

Yet, at the same time the government was pursuing its “Kurdish opening,” operations against Kurdish politicians and civil society leaders associated with the PKK began—and, much to the harm of AKP’s reception in the region, after the party had suffered fairly devastating losses in election. Local elections in March 2009 marked the first time the AKP had lost ground to Turkish nationalists since coming to power. Accusations of political revenge soon followed, as well as a claims on the part of Kurdish nationalists that the AKP’s aim was to eliminate the “bad Kurds (i.e., nationalist Kurds),” in order to force eventual assimilation. [A side note, but tragically ironic, if it was the government’s intent to eliminate nationalist Kurds from what some government officials called the “real Kurds,” it has been the PKK’s effort over the years to marginalize the more integrated Kurds—the PKK would use the term “assimilated”—from the nationalist Kurds, whom the PKK, in turn, considers the “ real Kurds.” The reality, of course, is that there is more than one reality, and that Kurds, qua individuals, get caught in the middle.] The PKK, as well as the BDP, have perpetuated, if not ramped up, this rhetoric of elimination since June’s election, making compromise all the more difficult. How can one negotiate with another party intent to eliminate you?

For the government’s part, there is increasingly less recognition of those Kurds who are nationalists as legitimate players with the right to participate in politics—of course, a fact not helped by the PKK’s intransigence when it comes to ending its violent campaign against Turkish state forces, many of which are conscripts or civilian police officers (or, in the most egregious cases, state-employed school teachers or family members and/or bystanders of PKK terrorism). Though the government has announced plans for yet another Kurdish opening, its new coordinated, rapid response military campaign against the PKK, which has unusually carried on throughout the winter months, seems armed with more sticks than carrots—and, again, the effect of that is a ratcheting up of the PKK/BDP’s rhetoric of elimination.

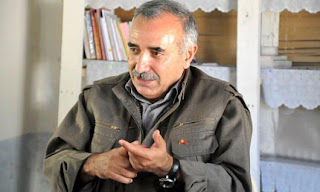

PHOTO from Rudaw

In an interview last week with Rudaw, the PKK’s leader in Kandil, Murat Karayilan, laid the blame of increased violence squarely at the feet of Prime Minister Erdogan. For Radikal columnist Cuneyt Ozdemir's take on the interview, click here. In Karayilan's mind, Erdogan has now taken control of the state: whereas before the prime minister could claim he could not control various elements of the state opposed to his agenda, in particular the Turkish Armed Forces and judiciary, according to Karayilan, the prime minister can no longer make that claim. Karayilan confirms negotiations with the government, and claims that the government would always explain the continued military and judicial operations against the PKK as out of its control, which again, according to Karayilan, they are not. Implying that negotiations were halted because the PKK realized the government’s lack of honesty as to its ability to halt operations against it, Karayilan naturally attempts to take the high ground while at the same time condemning the government’s plans for a second opening as insincere and, of course, ultimately aimed at destroying the Kurdish national movement and assimilating all Kurds.

Of course, the reality is that the government always used a mixture of carrots and sticks, and yes, the self-righteous attitude of Karayilan is to be expected. Yet, at the same time, the AKP’s situation is different than it was when it began talks with the PKK five years ago. The AKP now not only has control of the prime ministry, but has largely civilianized the Turkish Armed Forces and tightened its control over the judiciary, which less than four years ago almost brought about its closure. The AKP is, to a large extent, in control of the state.

Semih Idiz depicts the AKP as Janus-faced, looking at once to the future while caught up in the past. More optimistically than other critics, Idiz argues that while the party has made significant progress on the democracy and human rights front, including on the Kurdish question, it has too easily been caught in the traps of the past—thus, the result is often two steps forward, one step back. I do not contradict Idiz here, but do think the party, and Turkey, risks more than a slower march toward progress. The bold moves the AKP made in efforts to transform the Kurdish question, most significantly its efforts to accommodate a Kurdish cultural reality and its opening negotiations with the PKK, could easily result in a serious setback should the party continue its high-intensity security struggle (a look back to the past) without ensuring that the carrots the government is now offering are more than mere gestures—that the party is serious about granting constitutional recognition to Kurds as citizens of Turkey, and is intent to negotiate with the nationalists as to other demands related to federalism and autonomy, and do so, of course, with respect to all Kurds—not just the nationalists. The nationalists do not represent all Kurds, but neither can they be ignored.

Yet Karayilan is not correct here either. If Prime Minister Erdogan does wield control of the state, this still does not mean that the prime minister is necessarily in the position to make concessions, especially given divides within his own party on the Kurdish question and serious misgivings on the part of the Turkish public, which has had to deal with terrorist violence for more than twenty years. That Karayilan does not even begin to endeavor recognition of Deputy Prime Minister Bulent Arinc's statement that group rights for Kurds will be enshrined in the constitution, including much demanded rights to Kurdish language education, gives reason to doubt the role of the PKK as a peacemaker -- or, at least the role of Kandil. When talks of a possible ceasefire occurred this past July in conjunction with Ocalan's call for a "peace council," it was Karayilan who resisted and what followed was a violent attack on Turkish conscripts that seriously set back any hope for an emerging peace process.

It is difficult to blame Ankara for being fed up, and even more impossible not to recognize some glimmer of hope in the deputy prime minister's recent statements, even amidst continued operations against alleged members of the KCK, such as respected academic Busra Ersanli. What is sure is that ramped up rhetoric, paranoia, and lack of trust on both sides is sure to keep the conflict alive, especially as long as violence remains part of the equation. The AKP may be intent to so weaken the PKK by this summer that it will be forced to lay down arms (an unlikely result), but given the PKK's recent posturing, it will be difficult to realize the give-and-take between the two sides that would mollify the PKK's conviction the government is out to eliminate it and pave the way for future talks. The burden is not just on the AKP, but also Kandil.

No comments:

Post a Comment