PHOTO from Vatan

The parliament took up the proposed education law (see past post for background) yesterday just hours after 20,000 demonstrators gathered in Ankara's Tandogan Square to protest what opposition groups view as a unilateral attempt by the ruling AKP to overhaul the education system.

The law the AKP is trying to pass is publicly referred to as "4+4+4" because it seeks to make 12-year education mandatory for all children. Yet that is not the full story. Under the current system, public education is mandatory for the first eight years, after which students may opt to attend imam-hatip, or religious high schools that teach a mixture of standard education and theology, and which are subject to different standards -- and, naturally -- a different ideological/pedagogical atmosphere. The proposed law, which has been amended since my last post, also includes provisions that would pave the way for children to opt to attend imam-hatip as early as 10 years of age, as well as enter special vocational schools. The original law had included a measure that would allow children to opt into "open education," or home schooling, as early as 10 years of age. That provision has since been amended under pressure from women's another groups that introducing open education at such an early age would lead to an increase in child labor and young girls being kept from school to work at home -- a problem in conservative communities that activist groups have long sought to remedy.

The proposed system seeks to effectively divide education into three tiers -- first, middle, and high school. The government also plans to introduce a year before primary education akin to what in the United States is known as "pre-school," and which AKP politicians have haled as a major selling point of the new law. Under the proposal, children would also be able to join private religious education courses, often held during the summer, after their fourth year in school.

For AKP policymakers, the new system is to be celebrated not only as a means to further the quality of public education but also "democracy" -- a word much heralded by AKP politicians, but which for all intents and purposes, seems simply to mean rule by the majority, and a majority as the ruling party interprets it (for more on this, see this past post he AKP's sparring with TUSIAD, the leading business association in Turkey which has puts itself squarely in opposition to the new arrangements).

Much at the heart of the AKP's framing the issue is the fact that the current system is largely the product of the 1997 "postmodern coup" that toppled the country's former Islamist-led coalition, in which the AKP has its roots. Under military tutelage in the years after the coup, the government sought to guard secularism against what the generals saw as the rising tide of political Islam and the current education system was a major concern, in particular the increasing popularity of imam-hatip. The system prior to the coup allowed parents to place their children in imam-hatip at the age of 10, a policy to which the AKP is returning. It also forbade children to take private religious courses (for example, during summer vacation) before completing five years in school.

Though the reform process at the time was far from democratic and involved a major abuse of power by the military, as well as persecution of numerous educators and students haling from conservative Muslim backgrounds, the new policy did yield some positive results, including an increase in the enrollment rate of girls in the first eight years of public education (from 34% to 65%). While the coup-driven education reform of the late 1990s should in no way be celebrated, the AKP should at the least explain how its new policy will not seek to imperil the success of the past decade in this regard. Yet rather than explaining how the new system (or devising one alternative to that proposed) might build on increased enrollment rates while adopting a more sensitive approach to religion, the party has instead simply decried opponents of the law to be against "democracy."

Polarization over the new law reached a new high two weeks ago when the parliamentary commission responsible for education policy ramrodded the proposal through the commission amidst fistfights between the ruling party and the opposition. Knowing that debate could delay the law's passage through the commission, the AKP blockaded opposition party members' attendance in attempt to forestall efforts to frustrate passage to the parliament's general assembly.

Soon after the brawl, the opposition CHP petitioned to annul the commission's vote, arguing that procedural rules had been violated. Yet parliament speaker Cemil Cicek seems to have no intention of returning the law to commission, and the party's plans at this point are to pass the law in the general assembly by the end of the week.

The protests yesterday reveal just how divided Turkey is becoming. Speaking at Tandogan, CHP leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu said the law is not "4+4+4," but "8/2." Kilicdaroglu was referring to the two different standards of education children would be receiving after the first eight years (and, in reality, after the age of 10 given the planned introduction of vocational schools and imam-hatip at so young an age). Yet there is another element to the leader's words worth exploring.

Though some of the AKP's policies have aimed to strip national education of some of the more distressing nationalist/ideological aspects of public education (for example, military-designed national security education courses and celebrations of national youth day, which liberals have long considered quasi-fascist), the fact that the government's most recent effort seems to setup a system parallel to that of national education (that is, imam-hatip and vocational education), there is real concern that the secular/conservative divide could grow deeper.Further, there is the very real possibility that a large number of Turks (future voting citizens) as early as age 10 could receive an education that is sub-par when compared to their counterparts that finish 12 years of public eduction. While these students might be more likely to constitute the "pious generation" Erdogan envisioned a few weeks before the education debate started in full, it is highly unlikely that they would demonstrate the same level of political efficacy and sophistication as their more educated counterparts.

Among the groups protesting the new legislation at Tandogan is Egitem-Sen, the left-leaning teachers' union, as well as the Rightful Women's Platform and the Federation of Turkish Women's Associations. The Confederation of Public Sector Workers (KESK), of which Egitem-Sen is a part, is also present. Egitem-Sen has called for two days of teachers' strikes to demonstrate against the proposed law, and is the chief organizer of the demonstrations alongside the CHP.

Ankara's governor, who is a member of the AKP, has questioned the legality of the assembly, and though he has yet to break up the gathering, he has threatened to do so. The municipality has removed banners and placards put up in the environs -- a move CHP parliamentarian and women's rights defender Binnaz Toprak described as a violation of freedom of expression. And so it seems there is potential for the fighting in parliament to soon bleed onto the streets -- a country divided indeed, and with neither liberal nor consensual democracy anywhere in sight at the moment. For more coverage in English of yesterday's protests, click here.

Showing posts with label CHP. Show all posts

Showing posts with label CHP. Show all posts

Wednesday, March 28, 2012

Tuesday, February 28, 2012

"New" Survives

PHOTO from Radikal

CHP leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu more than weathered two extraordinary congresses held in the past two days. On Feb. 26, the party held its first convention, which was called by Kilicdaroglu in response to a petition by the old guard within the CHP that is attempting to defeat Kilicdaroglu and what the party's new leadership has called "the new CHP" (see past post). After having survived the first, the second convention was anti-climactic.

The CHP is Turkey's oldest party, and having undergone many transformations over the years, dates to Ataturk. In the 1990s and 2000s, the party had drifted from its earlier social democratic roots to embrace a traditional Kemalist/nationalist platform focused on secularism and defending the state against Kurdish separatism. During this time, the party was led by Deniz Baykal, who when I first started paying attention to Turkish politics, was regarded as a figure similar to the Energizer bunny -- he just would not go away. Yet all that changed in 2010 when a sex tape brought him down. The result was a party congress that brought forward Kemal Kilicdaroglu, an Alevi with a more progressive vision.

Though Kilicdaroglu is still far from what one might call progressive, he has also had a lot to deal with since coming to power (see past post) and the CHP has made tremendous strides to transform itself into something new. Sometimes it is hard be hopeful in regard to politics, but the shakeup in CHP offered some reason for optimism -- and, I think, continues to do so.

The congress convened with over 800 members, well over the 625 needed to establish a quorum among the 1,248 delegates. Baykal and party stalwart Onder Sav had attempted to wage a boycott of the convention, which would have essentially caused a crisis in confidence of Kilicdaroglu's leadership and brought him down. Luckily, they failed miserably, and Sav ended up giving a rather desperate-seeming and indignant press conference not far from the convention vowing that Kilicdaroglu would pay in the end.

Of the delegates, the breakdown between the old guard, loyal to Baykal and the old vision, approximates 400. Before the party's regular congress this summer, at which Kilicdaroglu will stand for re-election, many of these delegates will no longer be eligible to participate thanks to a rule regarding term limits.

Now that Kilicdaroglu has a significant feather in his cap, it can only be hoped that he will return the CHP to the more progressive positions it was taking before the election. At the convention, Kilicdaroglu promised to take on the issue of specially-authorized courts, though it lacks much clout in this regard, as well as fully embrace a social democratic and liberal version of Turkey.

The party also plans to strengthen internal party democracy, which has been lacking. Provisions in this regard include primary elections for parliamentarians, as well as open elections for positions in party branches. The CHP has also bolstered its gender quota from 25 to 33%, as well as introduced a youth quota of 10%.

CHP leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu more than weathered two extraordinary congresses held in the past two days. On Feb. 26, the party held its first convention, which was called by Kilicdaroglu in response to a petition by the old guard within the CHP that is attempting to defeat Kilicdaroglu and what the party's new leadership has called "the new CHP" (see past post). After having survived the first, the second convention was anti-climactic.

The CHP is Turkey's oldest party, and having undergone many transformations over the years, dates to Ataturk. In the 1990s and 2000s, the party had drifted from its earlier social democratic roots to embrace a traditional Kemalist/nationalist platform focused on secularism and defending the state against Kurdish separatism. During this time, the party was led by Deniz Baykal, who when I first started paying attention to Turkish politics, was regarded as a figure similar to the Energizer bunny -- he just would not go away. Yet all that changed in 2010 when a sex tape brought him down. The result was a party congress that brought forward Kemal Kilicdaroglu, an Alevi with a more progressive vision.

Though Kilicdaroglu is still far from what one might call progressive, he has also had a lot to deal with since coming to power (see past post) and the CHP has made tremendous strides to transform itself into something new. Sometimes it is hard be hopeful in regard to politics, but the shakeup in CHP offered some reason for optimism -- and, I think, continues to do so.

The congress convened with over 800 members, well over the 625 needed to establish a quorum among the 1,248 delegates. Baykal and party stalwart Onder Sav had attempted to wage a boycott of the convention, which would have essentially caused a crisis in confidence of Kilicdaroglu's leadership and brought him down. Luckily, they failed miserably, and Sav ended up giving a rather desperate-seeming and indignant press conference not far from the convention vowing that Kilicdaroglu would pay in the end.

Of the delegates, the breakdown between the old guard, loyal to Baykal and the old vision, approximates 400. Before the party's regular congress this summer, at which Kilicdaroglu will stand for re-election, many of these delegates will no longer be eligible to participate thanks to a rule regarding term limits.

Now that Kilicdaroglu has a significant feather in his cap, it can only be hoped that he will return the CHP to the more progressive positions it was taking before the election. At the convention, Kilicdaroglu promised to take on the issue of specially-authorized courts, though it lacks much clout in this regard, as well as fully embrace a social democratic and liberal version of Turkey.

The party also plans to strengthen internal party democracy, which has been lacking. Provisions in this regard include primary elections for parliamentarians, as well as open elections for positions in party branches. The CHP has also bolstered its gender quota from 25 to 33%, as well as introduced a youth quota of 10%.

Friday, February 10, 2012

Weakening Minority Rights in Parliament

PHOTO from Hurriyet Daily News

At a time when Turkey is gearing up to craft a new constitution, its parliament is currently drafting changes to its rules that would significantly shorten the period of debate, extend sessions into the weekend if necessary, and limit proposals to draft laws.

The ruling AKP is claiming the rules are intended to streamline debate and increase parliamentary efficiency while opposition parties are claiming the new regulations are intended to silence opposition voices (for specific changes, click here). The debate reached a climax yesterday when the CHP, the largest opposition party, stormed the rostrum after Speaker Cemil Cicek closed debate after a five hour standoff wherein CHP and BDP lawmakers shouted slogans against the speaker, forcing Cicek to call numerous recesses.

The eventual result was a fistfight after Cicek closed the session. Fistfights are not altogether uncommon in the parliament, and in 2001, a similar debate over rules left one parliamentarian dead of a heart attack after a fight broke out. Cicek has been trying for the past week to reach a compromise between the AKP and opposition parties, though his efforts have clearly failed.

All three opposition parties are united against the rules changes, and claim the AKP is attempting to fix the rules ahead of the constitutional draft being submitted to the general assembly in order to easily force the document out of parliament and submit it to referendum, as the party did the 2010 amendment package. Though the AKP is three votes shy of the 330 votes (3/5 majority) it needs to pass the new constitution in parliament and take it to referendum (as it did in 2010), the opposition fears that the AKP could well cobble together this majority rather than engage all parties in a more consensual process.

Clearly such an endeavor would hurt the legitimacy of a new constitution and certainly contradict the ruling party's stated objective of achieving the widest degree of consensus possible -- but, here again, the operative word is "possible," and efforts to build consensus will depend on just how the AKP interprets this mission, and how committed it will remain to it. A party operating with a solid 3/5 majority since its entrance to parliament in 2002, consensus-building has not exactly been the party's forté, nor has it, in all fairness, to any Turkish political party. For more on this point, see E. Fuat Keyman and Meltem Muftuler-Bac's recent article in the January issue of the Journal of Democracy.

The appropriateness of fist-fighting aside, the move to change the rules has led opposition parties to boycott the constitutional reconciliattion commission charged with framing a new civilian constitution, and has, in general, detracted from the commission's task-at-hand. The commission is comprised of 12 members (three from every party) and is designed to garner consensus among political parties and civil society.

At this phase of the re-drafting process, the commission is currently seeking proposals from politicians and civil society groups, which up until recently, could be viewed publicly on this website parliament setup in October. Yet at the beginning of February the commission decided to hide the substance of proposals being submitted in order to protect the names of individuals and groups submitting them since some were quite controversial. At the moment, only the names of individuals and groups submitting proposals are left on the site. For more, see this front-page article from the Jan. 27 edition of Milliyet.

At a time when Turkey is gearing up to craft a new constitution, its parliament is currently drafting changes to its rules that would significantly shorten the period of debate, extend sessions into the weekend if necessary, and limit proposals to draft laws.

The ruling AKP is claiming the rules are intended to streamline debate and increase parliamentary efficiency while opposition parties are claiming the new regulations are intended to silence opposition voices (for specific changes, click here). The debate reached a climax yesterday when the CHP, the largest opposition party, stormed the rostrum after Speaker Cemil Cicek closed debate after a five hour standoff wherein CHP and BDP lawmakers shouted slogans against the speaker, forcing Cicek to call numerous recesses.

The eventual result was a fistfight after Cicek closed the session. Fistfights are not altogether uncommon in the parliament, and in 2001, a similar debate over rules left one parliamentarian dead of a heart attack after a fight broke out. Cicek has been trying for the past week to reach a compromise between the AKP and opposition parties, though his efforts have clearly failed.

All three opposition parties are united against the rules changes, and claim the AKP is attempting to fix the rules ahead of the constitutional draft being submitted to the general assembly in order to easily force the document out of parliament and submit it to referendum, as the party did the 2010 amendment package. Though the AKP is three votes shy of the 330 votes (3/5 majority) it needs to pass the new constitution in parliament and take it to referendum (as it did in 2010), the opposition fears that the AKP could well cobble together this majority rather than engage all parties in a more consensual process.

Clearly such an endeavor would hurt the legitimacy of a new constitution and certainly contradict the ruling party's stated objective of achieving the widest degree of consensus possible -- but, here again, the operative word is "possible," and efforts to build consensus will depend on just how the AKP interprets this mission, and how committed it will remain to it. A party operating with a solid 3/5 majority since its entrance to parliament in 2002, consensus-building has not exactly been the party's forté, nor has it, in all fairness, to any Turkish political party. For more on this point, see E. Fuat Keyman and Meltem Muftuler-Bac's recent article in the January issue of the Journal of Democracy.

The appropriateness of fist-fighting aside, the move to change the rules has led opposition parties to boycott the constitutional reconciliattion commission charged with framing a new civilian constitution, and has, in general, detracted from the commission's task-at-hand. The commission is comprised of 12 members (three from every party) and is designed to garner consensus among political parties and civil society.

At this phase of the re-drafting process, the commission is currently seeking proposals from politicians and civil society groups, which up until recently, could be viewed publicly on this website parliament setup in October. Yet at the beginning of February the commission decided to hide the substance of proposals being submitted in order to protect the names of individuals and groups submitting them since some were quite controversial. At the moment, only the names of individuals and groups submitting proposals are left on the site. For more, see this front-page article from the Jan. 27 edition of Milliyet.

Sunday, February 5, 2012

A House Divided

Tensions between the stalwarts and the leading new guard in the opposition CHP continue in the lead-up to what could be two extraordinary congresses held back-to-back at the end of this month while CHP leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu continues to toughen his rhetoric against the ruling AKP government.

In January, dissidents within the CHP began to plan for an extraordinary party congress to challenge Kilicdaroglu's leadership (see past post) and successfully collected the necessary number of signatures from dissidents within the party to call for an extraordinary convention. Dissidents collected 362 signatures from among 1,250 delegates, 12 more than the 350 required to apply for the congress. The dissidents state that their aim is to bolster intra-party democracy, though their more likely aim is to challenge Kilicdaroglu. Among the dissidents' demands is a lowering of the number of delegates required to call for electing a new party chairman.

Outmaneuvering the dissidents, Kilicdaroglu called for an extraordinary congress of his own to be held before the dissidents. The congress is scheduled for Feb. 26, and will allow Kilicdaroglu to shape the agenda so that he might stave off dissident moves that would prove particularly damaging to his leadership. Allies of Kilicdaroglu claim their aim is to reach a compromise with the dissidents, though, of course, they are also driven by the need to preempt a resurgence of the old guard.

It is precisely this fear of a resurgence that has prompted Kilicdaroglu to retain the anti-democratic rules that he vowed to replace upon becoming party chair. While it is true that these promises were not met, as Vatan columnist Bilal Cetin points out, the party's lack of reform in this regard is also to some degree understandable given the fact that it is still very much fighting for its own survival. The dissidents are threatening to file legal action against Kilicdaroglu in an effort to forestall the convention, claiming that Kilicdaroglu's announcement of a Feb. 26 congress is a violation of the party's by-laws and the national Political Parties Law.

The move is also defensive on the part of the dissidents. Kilicdaroglu has plans to limit the number of terms CHP deputies can serve in parliament. At the moment, and unlike other parties (for instance, the AKP limits members to three terms), the CHP has no such rules. While more democratic, term limits are also a way for Kilicdaroglu to further consolidate his power within the parliament since most of the CHP deputies who would no longer be eligible are loyal to former party leader Deniz Baykal and Baykal's like-minded general secretary, Onder Sav.

Ratcheting Up the Rhetoric: Erdogan vs. Kilicdaroglu

Meanwhile, Kilicdaroglu has continued to ramp up his rhetoric against Erdogan, and his efforts reach outside of Turkey. Today's column in the Washington Post has Kilicdaroglu pointing to the eight elected members of parliament who are still under detention, as well as the issue of mass detentions in general. Kilicdaroglu also addresses the attempt in January of one particularly zealous prosecutor to remove the leader's parliamentary immunity after he compared the facility in which the two detained CHP parliamentarians are being held to a concentration camp. After the incident, Kilicdaroglu asked that his parliamentary immunity be removed, a call echoed once more in this morning's Post.

The AKP, hesitant to draw even more criticism, has attempted to defuse the situation and has and will likely make no such move to remove Kilicdaroglu's immunity. The tenuous position Kilicdaroglu holds within his own party, and to some degree, amidst the Turkish electorate, is enough, as he is not perceived as a threat despite the recent rhetorical grandstanding, which, as I wrote in the January post referenced above, has more to do with his position within his own political party rather than an effort to garner votes throughout the country.

Tensions between the two parties have escalated in recent months as AKP prosecutors have launched investigations into the financial dealings of the Izmir municipality, a CHP stronghold. Izmir Mayor Aziz Kocaoglu currently faces 397 years in prison on corruption charges, and similar investigations are also ongoing in Eskisehir and Istanbul's Adalar district, also CHP strongholds.

There was also an earlier attempt by the government to link the CHP to funds coming from German foundations to CHP and BDP-controlled municipalities that some officials alleged, without much evidence, were being channeled to the PKK.

Additionally, speculation is brewing about a possible investigation into the sex tape scandal that brought down Baykal in 2010. According to Kilicdaroglu, an investigation could be launched soon as some prosecutors hostile to the CHP seek to portray the release of the tape as the work of an illegal criminal organization, and thereby launch operations against the CHP similar to the KCK operations in which the BDP is currently embroiled. This is still largely rhetoric at the moment, but the accusations are getting increased media attention, especially in hardline Kemalist newspapers like Sozcu.

Seeking Solidarity with Europe

The CHP has also been active in seeking the support of fellow European socialists against what it is labeling as the encroaching authoritarianism of Erdogan and the AKP. The Socialist International condemned the recent legal action against Kilicdaroglu, issuing a declaration expressing its concern over freedom of expression and judicial independence. For its full statement, click here.

The party is also working with European politicians to establish direct dialogue between it and the European Union through joint working groups and other possible mechanisms. These efforts follow-up on a November trip Kilicdaroglu paid to Brussels, where met one-on-one with Enlargement Commissioner Stefan Fule. As Haberturk reports, CHP vice-president Faruk Logoglu has been following up on the initiative. This sort of outreach to Europe was unheard of in the days Baykal was party leader, and is one of many positive developments that has occurred under the auspices of the party's new leadership.

UPDATE I (2/13) -- The dissidents within CHP have re-scheduled their congress from March 1 to Feb. 27, the day after Kilicdaroglu is to hold his.

In January, dissidents within the CHP began to plan for an extraordinary party congress to challenge Kilicdaroglu's leadership (see past post) and successfully collected the necessary number of signatures from dissidents within the party to call for an extraordinary convention. Dissidents collected 362 signatures from among 1,250 delegates, 12 more than the 350 required to apply for the congress. The dissidents state that their aim is to bolster intra-party democracy, though their more likely aim is to challenge Kilicdaroglu. Among the dissidents' demands is a lowering of the number of delegates required to call for electing a new party chairman.

Outmaneuvering the dissidents, Kilicdaroglu called for an extraordinary congress of his own to be held before the dissidents. The congress is scheduled for Feb. 26, and will allow Kilicdaroglu to shape the agenda so that he might stave off dissident moves that would prove particularly damaging to his leadership. Allies of Kilicdaroglu claim their aim is to reach a compromise with the dissidents, though, of course, they are also driven by the need to preempt a resurgence of the old guard.

It is precisely this fear of a resurgence that has prompted Kilicdaroglu to retain the anti-democratic rules that he vowed to replace upon becoming party chair. While it is true that these promises were not met, as Vatan columnist Bilal Cetin points out, the party's lack of reform in this regard is also to some degree understandable given the fact that it is still very much fighting for its own survival. The dissidents are threatening to file legal action against Kilicdaroglu in an effort to forestall the convention, claiming that Kilicdaroglu's announcement of a Feb. 26 congress is a violation of the party's by-laws and the national Political Parties Law.

The move is also defensive on the part of the dissidents. Kilicdaroglu has plans to limit the number of terms CHP deputies can serve in parliament. At the moment, and unlike other parties (for instance, the AKP limits members to three terms), the CHP has no such rules. While more democratic, term limits are also a way for Kilicdaroglu to further consolidate his power within the parliament since most of the CHP deputies who would no longer be eligible are loyal to former party leader Deniz Baykal and Baykal's like-minded general secretary, Onder Sav.

Ratcheting Up the Rhetoric: Erdogan vs. Kilicdaroglu

Meanwhile, Kilicdaroglu has continued to ramp up his rhetoric against Erdogan, and his efforts reach outside of Turkey. Today's column in the Washington Post has Kilicdaroglu pointing to the eight elected members of parliament who are still under detention, as well as the issue of mass detentions in general. Kilicdaroglu also addresses the attempt in January of one particularly zealous prosecutor to remove the leader's parliamentary immunity after he compared the facility in which the two detained CHP parliamentarians are being held to a concentration camp. After the incident, Kilicdaroglu asked that his parliamentary immunity be removed, a call echoed once more in this morning's Post.

The AKP, hesitant to draw even more criticism, has attempted to defuse the situation and has and will likely make no such move to remove Kilicdaroglu's immunity. The tenuous position Kilicdaroglu holds within his own party, and to some degree, amidst the Turkish electorate, is enough, as he is not perceived as a threat despite the recent rhetorical grandstanding, which, as I wrote in the January post referenced above, has more to do with his position within his own political party rather than an effort to garner votes throughout the country.

Tensions between the two parties have escalated in recent months as AKP prosecutors have launched investigations into the financial dealings of the Izmir municipality, a CHP stronghold. Izmir Mayor Aziz Kocaoglu currently faces 397 years in prison on corruption charges, and similar investigations are also ongoing in Eskisehir and Istanbul's Adalar district, also CHP strongholds.

There was also an earlier attempt by the government to link the CHP to funds coming from German foundations to CHP and BDP-controlled municipalities that some officials alleged, without much evidence, were being channeled to the PKK.

Additionally, speculation is brewing about a possible investigation into the sex tape scandal that brought down Baykal in 2010. According to Kilicdaroglu, an investigation could be launched soon as some prosecutors hostile to the CHP seek to portray the release of the tape as the work of an illegal criminal organization, and thereby launch operations against the CHP similar to the KCK operations in which the BDP is currently embroiled. This is still largely rhetoric at the moment, but the accusations are getting increased media attention, especially in hardline Kemalist newspapers like Sozcu.

Seeking Solidarity with Europe

The CHP has also been active in seeking the support of fellow European socialists against what it is labeling as the encroaching authoritarianism of Erdogan and the AKP. The Socialist International condemned the recent legal action against Kilicdaroglu, issuing a declaration expressing its concern over freedom of expression and judicial independence. For its full statement, click here.

The party is also working with European politicians to establish direct dialogue between it and the European Union through joint working groups and other possible mechanisms. These efforts follow-up on a November trip Kilicdaroglu paid to Brussels, where met one-on-one with Enlargement Commissioner Stefan Fule. As Haberturk reports, CHP vice-president Faruk Logoglu has been following up on the initiative. This sort of outreach to Europe was unheard of in the days Baykal was party leader, and is one of many positive developments that has occurred under the auspices of the party's new leadership.

UPDATE I (2/13) -- The dissidents within CHP have re-scheduled their congress from March 1 to Feb. 27, the day after Kilicdaroglu is to hold his.

Friday, January 13, 2012

How Much Longer Can "New" Last?

PHOTO from Radikal

Since its disappointing election result in June, the opposition Republican People's Party (CHP) has been internally divided and hopelessly outmaneuvered on multiple fronts.

The delicate state in which the party and its widely perceived feckless leader, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, finds itself is particularly sad given that the CHP has dramatically transformed itself in the wake of the sex scandal that brought down its former stalwart leader, Deniz Baykal. In contrast to Baykal, who seemed opposed to anything in the slightest progressive, including the EU accession process, minority rights, and a more nuanced understanding of secularism (away from the antiquated and oppressive concept of laïcité), the "new CHP," as the party has since branded itself, is decidedly pro-EU, pro-minority rights, and open to renegotiating the old Kemalist framework of secularism. The party espouses a commitment to liberalism reminiscent of the old AKP, and in few places can one find a hint of the staunch nationalist chauvinism that once dominated its politics.

Yet the "new CHP" might not last much longer. Though the party had expected to win over 30 percent of the vote in June elections, it received just over 25 percent, and since then, some opinion polls show popular support diminishing. More troubling is that the old nationalist stalwarts, headed by Baykal and former party general-secretary Onder Sav, are waiting in the wings to re-assume control should the liberals fail. And fail they might. A petition originating last week has collected the necessary number of signatures to force the CHP to hold an extraordinary congress in March, at which time those Baykal and Sav are likely to attempt a challenge of Kilicdaroglu's leadership.

The call for an extraordinary congress comes at a time when Kilicdaroglu is fighting to appease those more sympathetic to the old guard of his party. These efforts include Kilicdaroglu's visits to Silivri Prison, where numerous alleged members of the Ergenekon organization are being detained on charges of terrorism. These include CHP parliamentarians Mustafa Balbay and Mehmet Haberal, who the CHP ran for parliament and placed high on their party list despite their association with Ergenekon and known nationalist views and much to the advantage of the AKP, which pointed to their election as evidence that the CHP had not changed at all.

Upon his Nov. 9 visit, Kilicdaroglu called Silivri Prison a concentration camp for those who disagreed with the government, and it is these remarks that prompted a zealous prosecutor to charge him with insulting state officials and attempting to influence the judiciary, both of which are illegal and broadly interpreted under the current Penal Code. The prosecutor also filed a request that Kilicdaroglu's parliamentary immunity be lifted. In a fiery denunciation of the charges against him, Kilicaroglu responded in turn that he wished hismmunity would be removed and filed a formal application to the effect so that he could stand trial to face the charges against him -- a move followed by 132 parliamentarians from his party. Kilicdaroglu further said that he could be the next to end up in Silivri Prison, and perhaps even at the gallows.

Yet it is highly unlikely that Prime Minister Erdogan will allow for the removal of Kilicdaroglu's immunity (for more on this, see Murat Yetkin's column, in Turkish), and in fact, Erdogan has spoken against it, accusing Kilicadaroglu of cheap theatrics. Careful not to attract more international criticism or be responsible for what could happen if Kilicdaroglu were brought to trial, Erdogan is instead hoping Kilicdaroglu will fall victim to the divisiveness within his own party. Plus, Erdogan does not have much to fear at the moment from the CHP, which due to circumstances largely beyond its control, has turned into more of a sideshow than a real contestant for power.

That said, Kilicdaroglu, like other progressive elements in the CHP, are in a difficult spot. If they are too progressive, they will lose support from staunch Kemalists sympathetic to the old guard views within their party; yet if they take up the cause of two rather unpopular figures (Balbay and Haberal) and move too much toward the old rhetoric, they are likely to lose the liberals who voted for them in the last election. Kilicdaroglu's most recent attempts to portray himself as a victim under threat of being sent to Silivri are an attempt to take a hardline and demonstrate solidarity with Balbay and Haberal while at the same time seize an opportunity to criticize the specially authorized courts the government has setup to try suspected Ergenekon suspects. Yet, in a large sector of the Turkish public's eyes, this gesturing is more likely to place Kilicdaroglu and the CHP in the camp of Balbay and Haberal rather than as true liberals who stand up for everyone's rights.

The CHP, for its part, is not sure where it stands. Before elections, the party called for an amendment to one of the three currently inviolable first three articles of the constitution that would remove ethnically chauvinist tracings from the current definition of Turkish citizenship (a key demand of nationalist Kurdish nationalists) only to return to the position that the first three articles should not be amended. Similarly, when the party boycotted parliament, it demanded the release of its own parliamentarians, saying little about the release of the six BDP-supported candidates also imprisoned and unable to take their seats.

Though these inconsistencies are no doubt a symptom of the democracy pains faced by the CHP as its new leadership struggles to revitalize the party and overturn Baykal's legacy (Baykal dominated the party for over 18 years), party officials should recognize that the increase it did make in its votes -- while shy from the 30 percent hoped for -- is the result of a more progressive, inclusive party that, at least in its campaign rhetoric, espoused hope for a "Turkey for everyone." The party did pick up votes from many liberals and progressives, a large number of whom have become disenchanted with the AKP and its increasing authoritarian tendencies. That said, this new support extended to the CHP is still incipient and not wide-reaching, and few voters, even if they voted for the party, trust it will deliver on the social democratic policies promised. Support for Kilicdaroglu, who simply does not compare to Erdogan at a rhetorical level, is probably lower.

So far, Erdogan has taken advantage of the CHP's dilemma. Kilicdaroglu, an Alevi with family ties to Dersim, where in 1937-8 over 10,000 Alevi (and Zaza) Kurds were killed in air strikes by Turkish forces, has long-proven to be more liberal on the Kurdish issue than the old guard within his party. The strikes occurred under the leadership of the CHP (though a much older, and obviously much different party), and in the last years of Ataturk's life. In November, in a brilliant political move, Erdogan apologized for the killings, a move sure to spark division within the CHP. Former CHP deputy chairman Onur Oymen's remarks toward Alevis had divided the party at the end of 2009 (before Kilicdaroglu came to power), and the prime minister knew it would divide the party once more, putting pressure on Kilicdaroglu at a time when he was simply trying to stay alive in his party and avoid an extraordinary party congress, which looks like it is now happening.

With Kilicdaroglu now evermore associated with Balbay and Haberal, especially given that both men were behind the CHP's boycott of parliament after the elections, Erdogan will now take credit for not removing the opposition leader's immunity -- for taking the high road. Kilicdaroglu will instead be let to fall on his own sword or that of Baykal, with whom Erdogan visited this past December, in order to, reportedly, discuss allowing Haberal to visit his dying mother.

Whether the "new CHP" will survive attempts by the stalwarts in its wings to bring back the old "Party of No" is yet to be seen, but is of critical importance at a time when anything liberal and progressive should be preserved. There has not been a viable opposition party in Turkey since the AKP came to power, which indubitably allowed the ruling party to consolidate its power over the past ten years. Though "the new CHP" is perhaps not yet viable, it is the closest thing Turkey has seen to a legitimate social democratic party since Bulent Ecevit's troubled Democratic Left Party in the 1990s. Baykal might no longer be holding the reins of the CHP, but it is not quite clear whether Kilicdaroglu is either, nor whether he will be able to hold onto power much longer.

Since its disappointing election result in June, the opposition Republican People's Party (CHP) has been internally divided and hopelessly outmaneuvered on multiple fronts.

The delicate state in which the party and its widely perceived feckless leader, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, finds itself is particularly sad given that the CHP has dramatically transformed itself in the wake of the sex scandal that brought down its former stalwart leader, Deniz Baykal. In contrast to Baykal, who seemed opposed to anything in the slightest progressive, including the EU accession process, minority rights, and a more nuanced understanding of secularism (away from the antiquated and oppressive concept of laïcité), the "new CHP," as the party has since branded itself, is decidedly pro-EU, pro-minority rights, and open to renegotiating the old Kemalist framework of secularism. The party espouses a commitment to liberalism reminiscent of the old AKP, and in few places can one find a hint of the staunch nationalist chauvinism that once dominated its politics.

Yet the "new CHP" might not last much longer. Though the party had expected to win over 30 percent of the vote in June elections, it received just over 25 percent, and since then, some opinion polls show popular support diminishing. More troubling is that the old nationalist stalwarts, headed by Baykal and former party general-secretary Onder Sav, are waiting in the wings to re-assume control should the liberals fail. And fail they might. A petition originating last week has collected the necessary number of signatures to force the CHP to hold an extraordinary congress in March, at which time those Baykal and Sav are likely to attempt a challenge of Kilicdaroglu's leadership.

The call for an extraordinary congress comes at a time when Kilicdaroglu is fighting to appease those more sympathetic to the old guard of his party. These efforts include Kilicdaroglu's visits to Silivri Prison, where numerous alleged members of the Ergenekon organization are being detained on charges of terrorism. These include CHP parliamentarians Mustafa Balbay and Mehmet Haberal, who the CHP ran for parliament and placed high on their party list despite their association with Ergenekon and known nationalist views and much to the advantage of the AKP, which pointed to their election as evidence that the CHP had not changed at all.

Upon his Nov. 9 visit, Kilicdaroglu called Silivri Prison a concentration camp for those who disagreed with the government, and it is these remarks that prompted a zealous prosecutor to charge him with insulting state officials and attempting to influence the judiciary, both of which are illegal and broadly interpreted under the current Penal Code. The prosecutor also filed a request that Kilicdaroglu's parliamentary immunity be lifted. In a fiery denunciation of the charges against him, Kilicaroglu responded in turn that he wished hismmunity would be removed and filed a formal application to the effect so that he could stand trial to face the charges against him -- a move followed by 132 parliamentarians from his party. Kilicdaroglu further said that he could be the next to end up in Silivri Prison, and perhaps even at the gallows.

Yet it is highly unlikely that Prime Minister Erdogan will allow for the removal of Kilicdaroglu's immunity (for more on this, see Murat Yetkin's column, in Turkish), and in fact, Erdogan has spoken against it, accusing Kilicadaroglu of cheap theatrics. Careful not to attract more international criticism or be responsible for what could happen if Kilicdaroglu were brought to trial, Erdogan is instead hoping Kilicdaroglu will fall victim to the divisiveness within his own party. Plus, Erdogan does not have much to fear at the moment from the CHP, which due to circumstances largely beyond its control, has turned into more of a sideshow than a real contestant for power.

That said, Kilicdaroglu, like other progressive elements in the CHP, are in a difficult spot. If they are too progressive, they will lose support from staunch Kemalists sympathetic to the old guard views within their party; yet if they take up the cause of two rather unpopular figures (Balbay and Haberal) and move too much toward the old rhetoric, they are likely to lose the liberals who voted for them in the last election. Kilicdaroglu's most recent attempts to portray himself as a victim under threat of being sent to Silivri are an attempt to take a hardline and demonstrate solidarity with Balbay and Haberal while at the same time seize an opportunity to criticize the specially authorized courts the government has setup to try suspected Ergenekon suspects. Yet, in a large sector of the Turkish public's eyes, this gesturing is more likely to place Kilicdaroglu and the CHP in the camp of Balbay and Haberal rather than as true liberals who stand up for everyone's rights.

The CHP, for its part, is not sure where it stands. Before elections, the party called for an amendment to one of the three currently inviolable first three articles of the constitution that would remove ethnically chauvinist tracings from the current definition of Turkish citizenship (a key demand of nationalist Kurdish nationalists) only to return to the position that the first three articles should not be amended. Similarly, when the party boycotted parliament, it demanded the release of its own parliamentarians, saying little about the release of the six BDP-supported candidates also imprisoned and unable to take their seats.

Though these inconsistencies are no doubt a symptom of the democracy pains faced by the CHP as its new leadership struggles to revitalize the party and overturn Baykal's legacy (Baykal dominated the party for over 18 years), party officials should recognize that the increase it did make in its votes -- while shy from the 30 percent hoped for -- is the result of a more progressive, inclusive party that, at least in its campaign rhetoric, espoused hope for a "Turkey for everyone." The party did pick up votes from many liberals and progressives, a large number of whom have become disenchanted with the AKP and its increasing authoritarian tendencies. That said, this new support extended to the CHP is still incipient and not wide-reaching, and few voters, even if they voted for the party, trust it will deliver on the social democratic policies promised. Support for Kilicdaroglu, who simply does not compare to Erdogan at a rhetorical level, is probably lower.

So far, Erdogan has taken advantage of the CHP's dilemma. Kilicdaroglu, an Alevi with family ties to Dersim, where in 1937-8 over 10,000 Alevi (and Zaza) Kurds were killed in air strikes by Turkish forces, has long-proven to be more liberal on the Kurdish issue than the old guard within his party. The strikes occurred under the leadership of the CHP (though a much older, and obviously much different party), and in the last years of Ataturk's life. In November, in a brilliant political move, Erdogan apologized for the killings, a move sure to spark division within the CHP. Former CHP deputy chairman Onur Oymen's remarks toward Alevis had divided the party at the end of 2009 (before Kilicdaroglu came to power), and the prime minister knew it would divide the party once more, putting pressure on Kilicdaroglu at a time when he was simply trying to stay alive in his party and avoid an extraordinary party congress, which looks like it is now happening.

With Kilicdaroglu now evermore associated with Balbay and Haberal, especially given that both men were behind the CHP's boycott of parliament after the elections, Erdogan will now take credit for not removing the opposition leader's immunity -- for taking the high road. Kilicdaroglu will instead be let to fall on his own sword or that of Baykal, with whom Erdogan visited this past December, in order to, reportedly, discuss allowing Haberal to visit his dying mother.

Whether the "new CHP" will survive attempts by the stalwarts in its wings to bring back the old "Party of No" is yet to be seen, but is of critical importance at a time when anything liberal and progressive should be preserved. There has not been a viable opposition party in Turkey since the AKP came to power, which indubitably allowed the ruling party to consolidate its power over the past ten years. Though "the new CHP" is perhaps not yet viable, it is the closest thing Turkey has seen to a legitimate social democratic party since Bulent Ecevit's troubled Democratic Left Party in the 1990s. Baykal might no longer be holding the reins of the CHP, but it is not quite clear whether Kilicdaroglu is either, nor whether he will be able to hold onto power much longer.

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

Rough Waters Ahead?

PHOTO from Radikal

Sunday's elections created what is perhaps the most representative parliament in the history of the Turkish Republic. Of the 87% of eligible Turkish voters who showed up to cast ballots, only 4.4% voted for parties were not ultimately elected to parliament. This is down from 13% in 2007 and 32% in 2002. This representation problem has been a function of small political parties being unable to meet the country's high 10% threshold required to enter parliament. (The Kurdish BDP is an exception to this rule since it has not run as a political party, but rather chosen to run candidates as independents. A difficult feat to pull off, the BDP won 36 MPs this parliamentary election cycle.)

However, though there are now few political parties in parliament, this does not mean Turkey is necessarily any less divided. In fact, each of the four political parties now represented have unique constituencies and platforms that do not necessarily square with each other or facilitate compromise. As the AKP vows to seek compromise and civil society input as it moves forward with re-drafting the country's 1982 constitution, which was drafted in the shadow of a dramatic coup in 1980, it is unclear just how successful it can and will be.

Assessing the BDP

Cengiz Candar argues in today's Radikal that what a " BDP opening" is needed, meaning that the AKP must accommodate the voices and politics of the Kurdish nationalist party. At the same time, Candar, who is joined by other liberal public intellectuals who support Kurdish political, civil, and cultural rights, argues that the BDP has not shown itself to be a positive player when it comes to adopting the conciliatory politics required to reach a solution to the age-old Kurdish problem.

As Henri Barkey elucidated at an event at the Carnegie Endowment today (podcast here), the BDP's victory is impressive in that it resulted not only from the support it receives in the southeast (and in Kurdish areas throughout the country), but also from its tremendous capacity to organize. Successfully unning independent candidates for parliament is no easy task, and basically required the party to apportion its support for specific candidates running at the provincial level and then organize voters to elect these candidates. For example, in Diyarbakir, where support for the BDP was high, BDP supporters were divided between the number of candidates the BDP thought it could successfully run. Such a strategy requires the BDP to perform a complicated electoral math in determining just how many candidates it can elect in the context of a complicated electoral system and successfully rally the vote behind these independent candidates.

Though the BDP's success should not be underestimated, it should also not be overplayed. As Candar explains, though the BDP has gotten better at electoral engineering, political support for the party has not necessarily increased. Further, it should not be forgotten that a significant number of Kurds voted for the AKP despite its heavy nationalist rhetoric (Candar estimates 42%). Had the AKP not run a nationalist campaign in an effort to run the MHP into the ground, the result might have been different. Candar also points attention to the factions the BDP has managed to bring together (for example, bringing leftists together with staunch Kurdish nationalists and pro-Kurdish conservatives like Altan Tan and Sereafettin Elci). According to Candar, though this coalition-building is taking place at the elite level, the BDP has not succeeded in doing so among voters.

Trouble Brewing

In the days after the election, the BDP used this mammoth victory to call for the release of PKK terrorist leader Abdullah Ocalan and direct negotiations with the PKK, actions sure to infuriate the vast majority of Turkish votes. In doing, the BDP is alienating itself from the larger electorate and adopting a divisive politics sure to further fuel the conflict.

At the same time, the AKP has paid little attention to the Kurdish problem, the existence of which the party denied during the campaign, and is instead focusing on moving onward with business as usual. The two positions combined create the conditions for a political crisis, which could come soon given that six of BDP's deputies are currently in jail and their eligibility to hold seats in parliament still up in the air.

Chief among these is Hatip Dicle, who was convicted in 2009 for disseminating PKK propaganda and whose candidacy was at the heart of the riots that enfolded at the end of April when the High Election Board (YSK) invalidated the candidacies of 11 BDP candidates (see April 21 post). On June 9, just three days before the elections, the Supreme Court of Appeals upheld Dicle's conviction. Though it was too late to remove his name from the ballot, the High Elections Board will decide whether he is able to serve in parliament.

The six BDP candidates currently jailed as part of the KCK operations (and who are awaiting trial) include Gulseren Yildirm, Ibrahim Ayhan, Selma Irmak, Faysal Sarayildiz, Kemal Aktas, and Dicle. Dicle's case is special since he is not only jailed and awaiting trial for alleged membership in the PKK (KCK), but has been convicted previously and been unable to attain the necessary paperwork required to allow him to enter parliament. The Constitution bars convicted persons from holding parliamentary office. (In addition to the six jailed BDP candidates, two CHP candidates and one MHP candidate, both recently elected, are also currently detained (for their role in Ergenekon).)

Meeting in Diyarbakir yesterday, the BDP called for the release of all six elected members and demanded the release of Ocalan. If the release of the six was not controversial enough, combining such a move with Ocalan's release is not politically savvy nor helpful for the peace process. Reaction in the Turkish press, nationalist and otherwise, has been harsh, and will likely only increase in intensity should a crisis with Dicle come to a head.

Will the AKP Seek Compromise?

Speculation is still high as to whether Prime Minister Erdogan will seek a presidential term in either 2012 or 2014 given the party's successful election result. While some observers argues the party's loss of seats and new need for compromise when it comes to amending the country's constitution renders null the possibility of a powerful Erdogan presidency, others conjecture the AKP will still be able to find the support it needs to change the constitution and empower Erdogan.

The prime minister has announced that he will not run for parliament again, and the AKP's current by-laws prevent him from being appointed to another term as prime minister. CSIS' Bulent Aliriza writes

Again, a key question here is whether and how the party will attempt to repair the bridges it has burnt with the large number of Kurdish voters to whom the party turned its back. Though the AKP failed to push the ultra-nationalist MHP beneath the 10% threshold, according to Barkey, any increase in the AKP's number of voters (above the 50% of the country who supported it in this election) will come from nationalist voters.

Getting these votes is dependent on how the party treats the Kurdish issue, and should it be intent to continue its nationalist rhetoric, the BDP opening for which Candar hopes is simply not going to come to fruition. At the same time, the AKP has expressed intent to negotiate with the CHP and the MHP, and there are those in the party who realize the necessity of dealing with the BDP, however unsavory and threatening its politics. At the party's parliamentary group meeting today, Erdogan re-affirmed his intent to move forward with the constitution and said he would personally supervise negotiations with the opposition and engagement with civil society.

Just how all of this will happen is yet to be seen, especially given that the next few weeks could prove difficult if the courts and the YSK prevent the release and entry of those elected candidates currently jailed. And, while Turkey might have a more representative parliament, a less divided country it is not.

Sunday's elections created what is perhaps the most representative parliament in the history of the Turkish Republic. Of the 87% of eligible Turkish voters who showed up to cast ballots, only 4.4% voted for parties were not ultimately elected to parliament. This is down from 13% in 2007 and 32% in 2002. This representation problem has been a function of small political parties being unable to meet the country's high 10% threshold required to enter parliament. (The Kurdish BDP is an exception to this rule since it has not run as a political party, but rather chosen to run candidates as independents. A difficult feat to pull off, the BDP won 36 MPs this parliamentary election cycle.)

However, though there are now few political parties in parliament, this does not mean Turkey is necessarily any less divided. In fact, each of the four political parties now represented have unique constituencies and platforms that do not necessarily square with each other or facilitate compromise. As the AKP vows to seek compromise and civil society input as it moves forward with re-drafting the country's 1982 constitution, which was drafted in the shadow of a dramatic coup in 1980, it is unclear just how successful it can and will be.

Assessing the BDP

Cengiz Candar argues in today's Radikal that what a " BDP opening" is needed, meaning that the AKP must accommodate the voices and politics of the Kurdish nationalist party. At the same time, Candar, who is joined by other liberal public intellectuals who support Kurdish political, civil, and cultural rights, argues that the BDP has not shown itself to be a positive player when it comes to adopting the conciliatory politics required to reach a solution to the age-old Kurdish problem.

As Henri Barkey elucidated at an event at the Carnegie Endowment today (podcast here), the BDP's victory is impressive in that it resulted not only from the support it receives in the southeast (and in Kurdish areas throughout the country), but also from its tremendous capacity to organize. Successfully unning independent candidates for parliament is no easy task, and basically required the party to apportion its support for specific candidates running at the provincial level and then organize voters to elect these candidates. For example, in Diyarbakir, where support for the BDP was high, BDP supporters were divided between the number of candidates the BDP thought it could successfully run. Such a strategy requires the BDP to perform a complicated electoral math in determining just how many candidates it can elect in the context of a complicated electoral system and successfully rally the vote behind these independent candidates.

Though the BDP's success should not be underestimated, it should also not be overplayed. As Candar explains, though the BDP has gotten better at electoral engineering, political support for the party has not necessarily increased. Further, it should not be forgotten that a significant number of Kurds voted for the AKP despite its heavy nationalist rhetoric (Candar estimates 42%). Had the AKP not run a nationalist campaign in an effort to run the MHP into the ground, the result might have been different. Candar also points attention to the factions the BDP has managed to bring together (for example, bringing leftists together with staunch Kurdish nationalists and pro-Kurdish conservatives like Altan Tan and Sereafettin Elci). According to Candar, though this coalition-building is taking place at the elite level, the BDP has not succeeded in doing so among voters.

Trouble Brewing

In the days after the election, the BDP used this mammoth victory to call for the release of PKK terrorist leader Abdullah Ocalan and direct negotiations with the PKK, actions sure to infuriate the vast majority of Turkish votes. In doing, the BDP is alienating itself from the larger electorate and adopting a divisive politics sure to further fuel the conflict.

At the same time, the AKP has paid little attention to the Kurdish problem, the existence of which the party denied during the campaign, and is instead focusing on moving onward with business as usual. The two positions combined create the conditions for a political crisis, which could come soon given that six of BDP's deputies are currently in jail and their eligibility to hold seats in parliament still up in the air.

Chief among these is Hatip Dicle, who was convicted in 2009 for disseminating PKK propaganda and whose candidacy was at the heart of the riots that enfolded at the end of April when the High Election Board (YSK) invalidated the candidacies of 11 BDP candidates (see April 21 post). On June 9, just three days before the elections, the Supreme Court of Appeals upheld Dicle's conviction. Though it was too late to remove his name from the ballot, the High Elections Board will decide whether he is able to serve in parliament.

The six BDP candidates currently jailed as part of the KCK operations (and who are awaiting trial) include Gulseren Yildirm, Ibrahim Ayhan, Selma Irmak, Faysal Sarayildiz, Kemal Aktas, and Dicle. Dicle's case is special since he is not only jailed and awaiting trial for alleged membership in the PKK (KCK), but has been convicted previously and been unable to attain the necessary paperwork required to allow him to enter parliament. The Constitution bars convicted persons from holding parliamentary office. (In addition to the six jailed BDP candidates, two CHP candidates and one MHP candidate, both recently elected, are also currently detained (for their role in Ergenekon).)

Meeting in Diyarbakir yesterday, the BDP called for the release of all six elected members and demanded the release of Ocalan. If the release of the six was not controversial enough, combining such a move with Ocalan's release is not politically savvy nor helpful for the peace process. Reaction in the Turkish press, nationalist and otherwise, has been harsh, and will likely only increase in intensity should a crisis with Dicle come to a head.

Will the AKP Seek Compromise?

Speculation is still high as to whether Prime Minister Erdogan will seek a presidential term in either 2012 or 2014 given the party's successful election result. While some observers argues the party's loss of seats and new need for compromise when it comes to amending the country's constitution renders null the possibility of a powerful Erdogan presidency, others conjecture the AKP will still be able to find the support it needs to change the constitution and empower Erdogan.

The prime minister has announced that he will not run for parliament again, and the AKP's current by-laws prevent him from being appointed to another term as prime minister. CSIS' Bulent Aliriza writes

The new constitution seems certain to usher in a presidential system, and it is clear that Erdogan intends to run for the presidency, either in 2012 or more likely in 2014. If he were to choose the latter date, he would then be in a position to implement his “Target 2023” election manifesto through the centennial of the Turkish Republic as president. However, the inability of the JDP to obtain 330 seats, which would have enabled Erdogan to get public approval for a new constitution in a referendum, presents an obstacle that needs to be overcome.Apart from the question of Erdogan continuance as the leading force in Turkish politics, the more immediate question is whether and just how the AKP will seek compromise and consensus on the constitution, especially given the likelihood of conflict over the jailed opposition candidates who have just been elected from parliament.

Again, a key question here is whether and how the party will attempt to repair the bridges it has burnt with the large number of Kurdish voters to whom the party turned its back. Though the AKP failed to push the ultra-nationalist MHP beneath the 10% threshold, according to Barkey, any increase in the AKP's number of voters (above the 50% of the country who supported it in this election) will come from nationalist voters.

Getting these votes is dependent on how the party treats the Kurdish issue, and should it be intent to continue its nationalist rhetoric, the BDP opening for which Candar hopes is simply not going to come to fruition. At the same time, the AKP has expressed intent to negotiate with the CHP and the MHP, and there are those in the party who realize the necessity of dealing with the BDP, however unsavory and threatening its politics. At the party's parliamentary group meeting today, Erdogan re-affirmed his intent to move forward with the constitution and said he would personally supervise negotiations with the opposition and engagement with civil society.

Just how all of this will happen is yet to be seen, especially given that the next few weeks could prove difficult if the courts and the YSK prevent the release and entry of those elected candidates currently jailed. And, while Turkey might have a more representative parliament, a less divided country it is not.

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

A Pyrhhic Victory?

I recently wrote a short entry on the elections for Democracy Digest, a project of the National Endowment for Democracy. An excerpt:

Increasingly, Turkey is polarized between those who support the AKP and those who do not. The AKP’s critics include not only the secular elite, but also liberals, Kurds and other minority groups, and others who fear the intolerance with which the party deals with difference and dissent.For the full entry, click here. The blog is a good way to monitor political development throughout the world.

However, the new parliament presents fresh opportunities for compromise and reconciliation. All parties agree that Turkey should adopt a new constitution, and given the CHP’s progressive turn, the country now has a genuine opportunity to pass a liberal democratic constitution that will respect and affirm the rights of all citizens.

Nevertheless, and despite Prime Minister Erdogan’s acceptance speech yesterday in which he vowed to seek compromise on a new constitution, it is possible, even likely, that the AKP will promote its agenda with minimal compromise and consultation (as it has in the past). Such a unilateral approach increases the likelihood of the new constitution entrenching the illiberal practices evident in the AKP’s current exercise of power, including the targeting of journalists, libel suits, increased reliance on executive and administrative orders, enhanced cabinet powers at the expense of parliament, limited minority rights, and restrictions on freedom of association and civil society.

Turkish civil society is crucial to ensuring that Erdogan seeks compromise with the other three political parties that have entered parliament. In this context, civil society will prove just as key to saving Turkish democracy as it did during the optimistic years after the EU accepted Turkey’s application for membership in 1999 and major reforms started coming down the pipe. Support for strengthening political parties and institution building has been enormously successful, but further progress is unlikely without funding and empowering civil society to hold the government and political parties in check and goad them to respond to democratic demands.

A democratic regression in Turkey will not only mark the end of a regional success story but also set back Islamist/conservative democrats in other Muslim states who view the AKP as an exemplar. As recent survey research attests, 66% of Arabs view Turkey as a democratic model.

Turkish democracy is neither a mission accomplished nor a lost cause. Authoritarian trends can be reversed and the AKP government may yet return to the more liberal politics of its inception. However, this will take serious work and dedication from the government, opposition political parties, and civil society. These elections and upcoming plans to draft a new constitution provide at once a strong impetus for reform and a new starting point.

Monday, June 13, 2011

A Country Divided

Cartoon from Hurriyet

Sounding the same refrain as last September's constitutional referendum, yesterday's election results reveal Turkey to be increasingly divided between those who support the ruling AKP government and those who do not.

Yesterday the AKP managed to increase its vote from the 46.58% it captured in 2007 parliamentary elections to 49.91%, though the party lost lost seats and its 3/5 majority in parliament (see yesterday's post).

Additionally, the AKP became the first party since the Democratic Party in the 1950s to win three consecutive parliamentary elections; however, unlike the Democratic Party, the AKP has become more popular each election, not less. Yet, while the results hint at the AKP's growing popularity, they also hint at a growing disconnect between the party's supporters and those who fear its burgeoning illiberal tendencies (see last Tuesday's post).

The Other Half

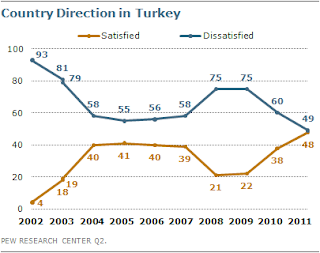

As echoed by the results of a recent Pew poll, Turkey is becoming an increasingly divided country. While those who support the AKP continue to enthusiastically return it to power, the other half (and it is literally half) of its population is deeply concerned with the direction in which the country is headed. The abyss between the two camps has grown in recent years, revealing a social phenomenon much more complicated than the narrative so often told in Western newspapers of a conflict between the ascendant Islamist middle class and the secular Kemalist elite.

Instead, what is happening in Turkey is that half the population solidly supports the AKP and its policies while the other half are becoming increasingly alienated from the party for a variety of reasons. This "other half" is not some unified Kemalist/secularist/nationalist opposition bloc, but rather represents a diverse array of different facets of Turkish society that have been left out of the AKP's increasingly hegemonic vision.

Of those opposed to the AKP, there are those concerned with the party's Turkish-Sunni chauvinism. These include not only members of a secular elite, but also Alevis (15 to 20 million people), Kurds (also 15 to 20 million people, though many Kurds are also Alevis), liberals (including Islamists), and leftists concerned about the AKP's neoliberal economic schemes. There are also plenty of observant Sunni Muslims who are nonetheless less pious than the AKP and/or increasingly concerned with the party's attempts to legislate its values. At the same time, there is a significant number of voters (~10%) for whom the AKP is not chauvinist enough. Most of these vote for the ultra-nationalist MHP.

The Next Steps

From Radikal

Starting with Refah in 1994, the AKP's antecedent, the AKP has gradually increased its votes since first elected office in 2002 with the one exception being the March 2009 local elections.

This is where the steps the AKP takes after the elections become crucial. Prime Minister Erdogan is determined to push through a new constitution that would institute a presidential system. Erdogan is widely thought to have designs on running for president should the changes come into being.

However, in a twist, though the AKP increased its share of the popular vote, it lost seats in parliament and is now short of the 3/5 majority it needs to unilaterally amend the constitution as it did last year. The loss of seats is a function of two factors, namely a high 10% threshold and a complicated system of closed-list proportional representation: an increase in the number of independent deputies associated with the Kurdish nationalist BDP and the increased number of voters in big cities where the party tends to do less well.

As a result of the shortfall, the AKP to some degree be pressured to compromise with opposition political parties if a new constitution is going to emerge, an objective supported by all political parties entering parliament.

That said, and despite Prime Minister Erdogan's acceptance speech yesterday in which he vowed to seek consensus as his government moves forward with a new constitution, it is possible, even likely, that the AKP will use its power to push forward its agenda with minimal compromise and consultation (as it has in the past). However, the risk, of course, is the way that power is enacted (targeting of journalists, libel suits, increased reliance on executive and administrative orders, more power to cabinet/less to parliament, limited minority rights, restrictions on association/NGO activity, etc.).

The most popular politician in the history of Turkish electoral politics, Erdogan has accomplished a tremendous electoral feat. It is more likely to encourage his appetite for power than to tame it. Power corrupts, and the more absolute the power, the more absolutely it corrupts.

Weep Not for the Opposition

And, where does the opposition stand -- and those who did not vote for the AKP? For one, it is unlikely the AKP will be able to further increase its vote. Given that the number of people unhappy with the direction in which Turkey is headed is the same number of people who did not vote for the AKP (see Pew Poll above), there is little headway the AKP can make in terms of winning additional votes -- basically, the party is maxed out.

All the same, the AKP's uncanny ability to turn nationalist then liberal -- only to do it all over again -- cannot be underestimated, and the party has a decent shot at maintaining its current numbers, especially if it decides to move again to the left so as to not be out-done by the CHP. However, I do believe the party's most recent bout of illiberalism, on full-display in its handling of the Ergenekon investigation, has burned many bridges, as did its extreme nationalist return in the past few months preceding the election.

There is little likelihood that bridges with more nationalist-inclined Kurds can be repaired given the ruling party's tenor this election cycle, especially given the failure of its Kurdish opening to deliver many concretes. Even less likely is that the party will win back the liberals and progressives who have been breaking ranks since 2005, many of whom have come to fear the party as a new authoritarian threat.

While the AKP might win some hardline nationalist votes from the MHP, it is unlikely to have much success here without losing a certain remainder of optimistic liberals who have continued to support the party for its economic successes and in spite of its illiberal tendencies.

The CHP

PHOTO from Radikal

Meanwhile, the CHP should regard its performance yesterday as a victory. "The new CHP," as the party has billed itself in the run up to the elections, managed to increase its vote share by 5% (a larger increase than the AKP) and gain 38 seats. Additionally, the CHP seems to have broadened its geographic reach, winning its party leader's home province of Tunceli while faring reasonably better in areas outside of its traditional strongholds. Support for the party might not be as deep in traditonally nationalist coastal enclaves (Antalya, Canakkale, and Izmir) as it once was, but the party has broadened its support beyond voters in these provinces while successfully moving toward establishing a different, much more liberal, pro-European electoral base.

Though no doubt disappointed, the CHP should realize it will take time for the Turkish public to trust it. A party in transition, the CHP had been up until a year ago an intolerant, oftentimes destructive force, providing people with little to no alternative but to vote for the AKP. There are likely plenty of Turkish voters who cast ballots for the AKP but are less than solid supporters; however, they do not trust the CHP either.