PHOTO from Milliyet

One of my favorite political/rhetorical theorists, Kenneth Burke, reckons rhetoric -- and, more specifically, the politics it facilitates -- as akin to theater. According to Burke, life and politics are theater, and we all, as political actors, are on a stage. Though accusing someone of making political theater is pejorative, for Burke, we all make theater. Think Arendt and her Greek-influenced notion of politics as action -- as individuals appearing to each other in public fora whereby they put forward their thought and ideas, and wherein those thoughts and ideas, though sometimes agonistically incommensurable, are negotiated in communication with others.

For Burke and Arendt, while we may all be actors on a stage or in a public forum, no one has the right to call places. In a liberal democracy, politicians, civil society activists, and citizens all have a right to express themselves in the public sphere -- to partake in politics on any range of issues without being bounded. Tracing the development of civil society's relation to the state, this sort of boundlessness is key to civil society's ability to challenge the state -- to have and take advantage of the space necessary to enact truly democratic politics capable of holding the state accountable to those it governs.

Yet, for many politicians in the AKP, this idea is strange -- and, for too many, anathema. See, for instance, the recent comments of AKP parliamentarian Nurettin Canikli in response to the Turkish Businessmen and Industrialists' Association (TUSIAD)'s criticisms of the government's plans for 4+4+4 education reform. TUSIAD is one of the most important NGOs for Turkey, and has proven a tremendous force for the country's European Union accession process and the democratic reform/EU harmonization packages that have so changed Turkey (and, which, contrary to so much of the coverage one sees in Western media, commenced in 1999, more than two years before the ruling AKP came to power).

According to Canikli, TUSIAD, as a business association, has the right only to speak on matters of business and economic policy -- not education. For Canikli, it is no matter that the quality of education is indubitably connected to both, as the boundaries he would place on the organization are quite strict. But that said, why might TUSIAD not also be able to speak on other important political issues, including human rights, the Kurdish conflict, freedom of the press, and a host of other issues on which it has in the past, should, and hopefully will continue to voice its opinion? For Canikli, if this happens, the association "should not only throw punches, but be ready to get punched."

Canikli, in stronger terms, is echoing remarks Prime Minister Erdogan delivered last Tuesday at his party's parliamentary group meeting. Though Erdogan laid off the issue during yesterday's party meeting, the prime minister stirred a series of heated exchanges between the AKP and TUSIAD when Erdogan lashed into the organization, accusing it of being a supporter of the Feb. 28 process (Turkey's 1997 postmodern coup) and telling it to "mind its own business." TUSIAD responded with a calmly generic explanation of the important role civil society plays in a democracy, and rhetorical clashes between the organization and the AKP continued throughout the week. (Here, and to his credit, note that on Saturday President Gul defended TUSIAD's role to engage in the education debate.)

Though there is nothing necessarily improper about a civil exchange of views between the government and civil society organizations, there is something quite wrong about the government circumscribing the activities of organizations, a frequent action taken by authoritarian governments around the world to restrict civil society and the freedoms it enjoys under international law. Here, it should be noted that associations law in Turkey has undergone a series of meaningful reforms under AKP rule, including a major overhaul in 2004 to the Associations Law. The AKP should be lauded for these changes, but rhetoric such as that coming from Erdogan and Canikli is threatening.

In stirring defense of liberalism and the role of civil society, Milliyet columnist Mehmet Tezkan digs into the implication of Canikli's comments: that civil society organizations might only speak on issues related to their particular focus. According to Canikli, this would mean labor unions speak on workers' rights, bar associations speak only about matters of the judiciary, and doctors' associations speak only about medical issues. Such narrowly consigned responsibilities not only restricts the space in which civil society may act, but to some extent, also neutralizes them. Canikli seems to be saying that if civil society organizations get involved in politics, there will be consequences. Doing so not only sends a signal that civil society organizations should be apolitical, but that there might indeed be costs for being political.

If politicians in the government wish to criticize TUSIAD and other organizations within the public sphere, they should, of course, be free to do so. Yet, if these "punches" involve restrictive measures such as libel suits, criminal charges, and troubles registering and operating, there is a problem. Given Prime Minister Erdogan and others' understanding of the role of the press, there is little reason to think that the government's approach to civil society is much different -- and, indeed, leaders of numerous civil society organizations, at least in regard to the Kurdish problem, have been rounded up alongside journalists. Taking on an organization with the kind of international clout of TUSIAD is a different matter, though Erdogan and Canikli's statements in regard to the organization are revealing of the AKP's liberal democratic deficit (not that many political parties have proved much better upon coming to power).

This is the first clash this year between the AKP and TUSIAD, and the vitriol of Erdogan's rhetoric has raised serious eyebrows given that TUSIAD is a mainline pro-reform/pro-Europe organization that has in the past loaned support to the AKP's reform initiatives. In 2010, before the country's constitutional referendum in September, Prime Minister Erdogan demanded that TUSIAD take a stand for or against the constitution, arguing that those who stayed neutral would be "eliminated." EU Chief Negotiator Egeman Bagis followed up, declaring that he would challenge "the mental health and patriotism of anyone who intended to vote against" the referendum.

TUSIAD's position at the time was that Turkey needed a brand new constitution -- not simply a series of amendments designed to benefit the AKP. It should be remembered here that the amendments in 2010 were largely aimed to break the old establishment's hand on the judiciary, and in many ways, have since allowed the government to exert increased control of the organization. I know several Turks who opted to boycott or vote no against the referendum given these remarks and others like them. The latest set of exchanges is but a continuation of what has become prime minister's increasingly hostile stance toward the organization. More evidence of a rift between the AKP and TUSIAD emerged this week when news broke that a joint panel the two were planning to hold this month in Mardin had been cancelled.

And so what of the rhetoric of elimination? It is curious that Erdogan used this word when it also is the main accusation launched by Kurdish nationalists against the government -- they claim the government is trying to eliminate them, too. If the AKP respects these views, why the rhetoric? Is it mere populism against organizations like TUSIAD that are perceived by some AKP supporters as "elite"? Is it the prime minister's well-known tendency for rhetorical lavishes, and what many consider to be his quick temper? The government is clearly not intent to eliminate TUSIAD, but will it respect the organization and value its opinions? Most are not holding their breath.

The new film Fetih: 1453, which depicts the Ottoman conquest of Istanbul, has been used in the past two weeks as political capital against what Erdogan's critics receive is his sultan-like attitude toward politics. In the past couple weeks, videos have been circulating on YouTube and elsewhere of the film's caricature of Fatih Sultan Mehmet, the great Ottoman conqueror, juxtaposed with Erdogan (like this one). And while sultanism is in no way unique to Turkey or to the AKP in Turkey (the country's history of political leadership is a great testament to the truth of Lord Acton's famous axiom), the sheer number and intensity of these criticism and others like them represent a shift in how those fifty percent whom Erdogan and the AKP do not represent (see my election analysis) are increasingly alienated and wary at the prospect of the AKP's seeming strict majoritarian conception of democracy.

Some AKP politicians, including Erdogan, often seem baffled by this. Are they not democratizing the country? Have they not led the country's economy to be one of the strongest in Europe and the Middle East? Is Turkey not a great success story to be modeled elsewhere in the world? One might expect these party officials to bow down in gratitude to Erdogan as Orthodox Greeks do to Fatih Sultan Mehmet in 1453.

Such disbelief is not altogether uncommon for politicians who, often well-intentioned, place ends over means, and arrogantly, if not condescendingly, approach politics as if they know what is best for the direction of the country they govern and the citizens therein. But there is no such ijtihad. The prime minister and other AKP officials, not to mention those in opposition parties (which have their own democratic deficits and sultanist legacies!), represent the people -- they are not elected to tell the people what is best for them, or so says many of the criticisms launched against the party.

Yet the AKP and its dominant narrative of conquest and victimage (see past post) continues. Too often not only Prime Minister Erdogan, but all Turkish politicians, seem like great figures on a stage, players in some great drama that ordinary Turks simply sit back and watch. But real democratic politics, while perhaps dramatic as Burke argues, involve the citizens, too -- the citizens are players, too (not mere spectators), there is no director, and most importantly, no one gets to call places. No one can simply be eliminated.

(Note: An incomplete, draft version of this post appeared earlier today when I accidentally hit "Publish" instead of "Save Draft." Hopefully this complete version reads better, and makes a bit more sense.)

UPDATE I (3/8) -- Hurriyet Daily News columnist Gila Benmayor offers a bit more perspective on the recent clash between TUSIAD and the government, as well as criticism of the government's rushed attempt at this bill. As Benmayor argues, this is once again another example of the government pushing through massive reform packages with little consultation of civil society, especially civil society groups with whom it disagrees. The education package has now also lost the support of the Education Reform Initiative (ERG), which again, is not a Kemalist organization diametrically opposed to the AKP, but a moderate/reformist group that adopts a practical and non-ideological approach to the potential harms of the proposed legislation.

Showing posts with label Constitutional Reforms. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Constitutional Reforms. Show all posts

Wednesday, March 7, 2012

Friday, February 10, 2012

Weakening Minority Rights in Parliament

PHOTO from Hurriyet Daily News

At a time when Turkey is gearing up to craft a new constitution, its parliament is currently drafting changes to its rules that would significantly shorten the period of debate, extend sessions into the weekend if necessary, and limit proposals to draft laws.

The ruling AKP is claiming the rules are intended to streamline debate and increase parliamentary efficiency while opposition parties are claiming the new regulations are intended to silence opposition voices (for specific changes, click here). The debate reached a climax yesterday when the CHP, the largest opposition party, stormed the rostrum after Speaker Cemil Cicek closed debate after a five hour standoff wherein CHP and BDP lawmakers shouted slogans against the speaker, forcing Cicek to call numerous recesses.

The eventual result was a fistfight after Cicek closed the session. Fistfights are not altogether uncommon in the parliament, and in 2001, a similar debate over rules left one parliamentarian dead of a heart attack after a fight broke out. Cicek has been trying for the past week to reach a compromise between the AKP and opposition parties, though his efforts have clearly failed.

All three opposition parties are united against the rules changes, and claim the AKP is attempting to fix the rules ahead of the constitutional draft being submitted to the general assembly in order to easily force the document out of parliament and submit it to referendum, as the party did the 2010 amendment package. Though the AKP is three votes shy of the 330 votes (3/5 majority) it needs to pass the new constitution in parliament and take it to referendum (as it did in 2010), the opposition fears that the AKP could well cobble together this majority rather than engage all parties in a more consensual process.

Clearly such an endeavor would hurt the legitimacy of a new constitution and certainly contradict the ruling party's stated objective of achieving the widest degree of consensus possible -- but, here again, the operative word is "possible," and efforts to build consensus will depend on just how the AKP interprets this mission, and how committed it will remain to it. A party operating with a solid 3/5 majority since its entrance to parliament in 2002, consensus-building has not exactly been the party's forté, nor has it, in all fairness, to any Turkish political party. For more on this point, see E. Fuat Keyman and Meltem Muftuler-Bac's recent article in the January issue of the Journal of Democracy.

The appropriateness of fist-fighting aside, the move to change the rules has led opposition parties to boycott the constitutional reconciliattion commission charged with framing a new civilian constitution, and has, in general, detracted from the commission's task-at-hand. The commission is comprised of 12 members (three from every party) and is designed to garner consensus among political parties and civil society.

At this phase of the re-drafting process, the commission is currently seeking proposals from politicians and civil society groups, which up until recently, could be viewed publicly on this website parliament setup in October. Yet at the beginning of February the commission decided to hide the substance of proposals being submitted in order to protect the names of individuals and groups submitting them since some were quite controversial. At the moment, only the names of individuals and groups submitting proposals are left on the site. For more, see this front-page article from the Jan. 27 edition of Milliyet.

At a time when Turkey is gearing up to craft a new constitution, its parliament is currently drafting changes to its rules that would significantly shorten the period of debate, extend sessions into the weekend if necessary, and limit proposals to draft laws.

The ruling AKP is claiming the rules are intended to streamline debate and increase parliamentary efficiency while opposition parties are claiming the new regulations are intended to silence opposition voices (for specific changes, click here). The debate reached a climax yesterday when the CHP, the largest opposition party, stormed the rostrum after Speaker Cemil Cicek closed debate after a five hour standoff wherein CHP and BDP lawmakers shouted slogans against the speaker, forcing Cicek to call numerous recesses.

The eventual result was a fistfight after Cicek closed the session. Fistfights are not altogether uncommon in the parliament, and in 2001, a similar debate over rules left one parliamentarian dead of a heart attack after a fight broke out. Cicek has been trying for the past week to reach a compromise between the AKP and opposition parties, though his efforts have clearly failed.

All three opposition parties are united against the rules changes, and claim the AKP is attempting to fix the rules ahead of the constitutional draft being submitted to the general assembly in order to easily force the document out of parliament and submit it to referendum, as the party did the 2010 amendment package. Though the AKP is three votes shy of the 330 votes (3/5 majority) it needs to pass the new constitution in parliament and take it to referendum (as it did in 2010), the opposition fears that the AKP could well cobble together this majority rather than engage all parties in a more consensual process.

Clearly such an endeavor would hurt the legitimacy of a new constitution and certainly contradict the ruling party's stated objective of achieving the widest degree of consensus possible -- but, here again, the operative word is "possible," and efforts to build consensus will depend on just how the AKP interprets this mission, and how committed it will remain to it. A party operating with a solid 3/5 majority since its entrance to parliament in 2002, consensus-building has not exactly been the party's forté, nor has it, in all fairness, to any Turkish political party. For more on this point, see E. Fuat Keyman and Meltem Muftuler-Bac's recent article in the January issue of the Journal of Democracy.

The appropriateness of fist-fighting aside, the move to change the rules has led opposition parties to boycott the constitutional reconciliattion commission charged with framing a new civilian constitution, and has, in general, detracted from the commission's task-at-hand. The commission is comprised of 12 members (three from every party) and is designed to garner consensus among political parties and civil society.

At this phase of the re-drafting process, the commission is currently seeking proposals from politicians and civil society groups, which up until recently, could be viewed publicly on this website parliament setup in October. Yet at the beginning of February the commission decided to hide the substance of proposals being submitted in order to protect the names of individuals and groups submitting them since some were quite controversial. At the moment, only the names of individuals and groups submitting proposals are left on the site. For more, see this front-page article from the Jan. 27 edition of Milliyet.

Saturday, January 14, 2012

Erdogan: President in 2014

PHOTO from Milliyet

This week the parliament's constitutional commission reached consensus to hold the country's first presidential elections in 2014. The decision allows Prime Minister Erdogan, who under the AKP's by-laws cannot continue to serve as leader of his party after 2015, to run for president. This would allow Erdogan to stay at the top of the political scene and work to realize his plans for Turkey's centennial in 2023.

This calculus is likely behind Erodgan's desire for a strong presidential system modeled on the United States and/or France, a move that would require a drastic reworking of Turkey's parliamentary system but might well be up for debate as parliament continue to work on provisions for a new constitution to replace the 1982 constitution drafted under military tutelage.

Yet enacting a presidential system will not be easy given that the AKP is shy of the two-thirds majority required to unilaterally pass amendments to the constitution, as well as the three-fifths majority needed to pass amendments and then take them to referendum. Amendments passed in this way require only a simple majority, which the AKP, as it did in September 2010, would likely have little difficult attaining. That said, the party is just three votes shy of the three-fifths needed (it currently has 327 seats of 330) to bring amendments to referendum.

So why is this week's decision so important? When Turkey amended its constitution in 2007 to hold popular presidential elections (before presidents were elected by parliament), the law was also changed to allow two consecutive five-year terms rather than one seven-year term. The question that is now near decided (parliament still needs to vote on the measure) is whether the new law applies to President Gul. Would Gul serve one seven-year term? Or, would he serve one five-year term and then be allowed to run for re-election, a move that would frustrate Erdogan's ambitions and remove him from the top of Turkish politics after 2014?

Though the delay deciding the issue essentially de facto scheduled elections for 2014 since there was little possibility of holding elections this year, the matter is now more decided. Now the question is more what will happen to the AKP after Erdogan becomes president. Will President Gul take the post or will it go to someone more junior over whom Erdogan can exert control (or, to a candidate like Deputy Prime Minister Bulent Arinc, who recently sided with Gul over Erdogan when the two were divided over a law reducing the penalty for match-fixing and over whom it might be more difficult for Erdogan to assert control)? If the latter is to happen, parliamentary elections will have to be moved from 2015, for when they are currently scheduled, to a year before, meaning that Turkey would hold presidential, parliamentary, and local elections in the same year. And, just as important, will Erdogan be able to enact his constitutional vision and expand his power after 2014?

The Radikal story linked to above has the details about the new law.

UPDATE I (1/26/12) -- President Gul has approved the new law fixing his term to seven years, and so setting Turkey's next presidential elections for 2014. The new law was passed quickly by parliament on Jan. 19 despite opposition from the CHP, which is still deciding whether it will challenge the legislation at the Constitutional Court. Prime Minister Erdogan is thus cleared to run for president in 2014, becoming the first popularly elected president. Erdogan will be allowed to serve two five-year terms, and if he wins a second, he could well be president when Turkey celebrates its centennial in 2023.

This week the parliament's constitutional commission reached consensus to hold the country's first presidential elections in 2014. The decision allows Prime Minister Erdogan, who under the AKP's by-laws cannot continue to serve as leader of his party after 2015, to run for president. This would allow Erdogan to stay at the top of the political scene and work to realize his plans for Turkey's centennial in 2023.

This calculus is likely behind Erodgan's desire for a strong presidential system modeled on the United States and/or France, a move that would require a drastic reworking of Turkey's parliamentary system but might well be up for debate as parliament continue to work on provisions for a new constitution to replace the 1982 constitution drafted under military tutelage.

Yet enacting a presidential system will not be easy given that the AKP is shy of the two-thirds majority required to unilaterally pass amendments to the constitution, as well as the three-fifths majority needed to pass amendments and then take them to referendum. Amendments passed in this way require only a simple majority, which the AKP, as it did in September 2010, would likely have little difficult attaining. That said, the party is just three votes shy of the three-fifths needed (it currently has 327 seats of 330) to bring amendments to referendum.

So why is this week's decision so important? When Turkey amended its constitution in 2007 to hold popular presidential elections (before presidents were elected by parliament), the law was also changed to allow two consecutive five-year terms rather than one seven-year term. The question that is now near decided (parliament still needs to vote on the measure) is whether the new law applies to President Gul. Would Gul serve one seven-year term? Or, would he serve one five-year term and then be allowed to run for re-election, a move that would frustrate Erdogan's ambitions and remove him from the top of Turkish politics after 2014?

Though the delay deciding the issue essentially de facto scheduled elections for 2014 since there was little possibility of holding elections this year, the matter is now more decided. Now the question is more what will happen to the AKP after Erdogan becomes president. Will President Gul take the post or will it go to someone more junior over whom Erdogan can exert control (or, to a candidate like Deputy Prime Minister Bulent Arinc, who recently sided with Gul over Erdogan when the two were divided over a law reducing the penalty for match-fixing and over whom it might be more difficult for Erdogan to assert control)? If the latter is to happen, parliamentary elections will have to be moved from 2015, for when they are currently scheduled, to a year before, meaning that Turkey would hold presidential, parliamentary, and local elections in the same year. And, just as important, will Erdogan be able to enact his constitutional vision and expand his power after 2014?

The Radikal story linked to above has the details about the new law.

UPDATE I (1/26/12) -- President Gul has approved the new law fixing his term to seven years, and so setting Turkey's next presidential elections for 2014. The new law was passed quickly by parliament on Jan. 19 despite opposition from the CHP, which is still deciding whether it will challenge the legislation at the Constitutional Court. Prime Minister Erdogan is thus cleared to run for president in 2014, becoming the first popularly elected president. Erdogan will be allowed to serve two five-year terms, and if he wins a second, he could well be president when Turkey celebrates its centennial in 2023.

Thursday, January 5, 2012

Ozel Regrets "Terrorist" Label

PHOTO from Milliyet

Milliyet's Fikret Bila has run an interview with Chief of General Staff Necdet Ozel in which the head of the Turkish Armed Forces says he would not like to call PKK fighters "terrorists" since they, too, are citizens of Turkey.

According to Ozel, many PKK fighters have been deceived, a fact which the top general laments at the same time he gives casualty figures of how many terrorists have been killed in the past six months. Turkish forces in Turkey's near 18-year conflict with the PKK. That number is at 165, according to Ozel, while 112 have surrendered and another 50 have been captured.

Ozel's intimation that PKK fighters should not be labeled as "terrorists" has infuriated many Turks, and nationalist-minded bloggers are clamoring to criticize Ozel as ineffective, and many not simply vis-á-vis the Kurdish question, but in regard to the treatment of army generals who have been arrested in the ongoing Ergenekon investigations.

In the interview, Ozel also dismissed reports that the PKK has adopted a truce, arguing that the opposite is in fact true and that PKK operations have continued throughout the winter. He also said unequivocally that the Turkish Armed Forces were in no way involved in the negotiations between MIT and the PKK that seem to have ended at the end of 2009 or beginning of 2010. Ozel further states that he is against recognizing Kurdish as an official language or integrating it into school education and using it to administer public services.

The general goes on to state that the United States has provided assistance from northern Iraq, though the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) has done little to assist with the situation. Iraqi officials have told Ankara that there is little they can do (see an account of TRT's interview, in Turkish, with Iraq Vice President Tariq Hashimi on Oct. 30). Meanwhile Iraqi President Jalal al-Talabani and KRG president Massoud Barzani, much to the likely frustration of Turkish officials, continue to dialogue with the BDP, urging the party, albeit without much visible success, toward peace.

Milliyet's Fikret Bila has run an interview with Chief of General Staff Necdet Ozel in which the head of the Turkish Armed Forces says he would not like to call PKK fighters "terrorists" since they, too, are citizens of Turkey.

According to Ozel, many PKK fighters have been deceived, a fact which the top general laments at the same time he gives casualty figures of how many terrorists have been killed in the past six months. Turkish forces in Turkey's near 18-year conflict with the PKK. That number is at 165, according to Ozel, while 112 have surrendered and another 50 have been captured.

Ozel's intimation that PKK fighters should not be labeled as "terrorists" has infuriated many Turks, and nationalist-minded bloggers are clamoring to criticize Ozel as ineffective, and many not simply vis-á-vis the Kurdish question, but in regard to the treatment of army generals who have been arrested in the ongoing Ergenekon investigations.

In the interview, Ozel also dismissed reports that the PKK has adopted a truce, arguing that the opposite is in fact true and that PKK operations have continued throughout the winter. He also said unequivocally that the Turkish Armed Forces were in no way involved in the negotiations between MIT and the PKK that seem to have ended at the end of 2009 or beginning of 2010. Ozel further states that he is against recognizing Kurdish as an official language or integrating it into school education and using it to administer public services.

The general goes on to state that the United States has provided assistance from northern Iraq, though the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) has done little to assist with the situation. Iraqi officials have told Ankara that there is little they can do (see an account of TRT's interview, in Turkish, with Iraq Vice President Tariq Hashimi on Oct. 30). Meanwhile Iraqi President Jalal al-Talabani and KRG president Massoud Barzani, much to the likely frustration of Turkish officials, continue to dialogue with the BDP, urging the party, albeit without much visible success, toward peace.

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

A Pyrhhic Victory?

I recently wrote a short entry on the elections for Democracy Digest, a project of the National Endowment for Democracy. An excerpt:

Increasingly, Turkey is polarized between those who support the AKP and those who do not. The AKP’s critics include not only the secular elite, but also liberals, Kurds and other minority groups, and others who fear the intolerance with which the party deals with difference and dissent.For the full entry, click here. The blog is a good way to monitor political development throughout the world.

However, the new parliament presents fresh opportunities for compromise and reconciliation. All parties agree that Turkey should adopt a new constitution, and given the CHP’s progressive turn, the country now has a genuine opportunity to pass a liberal democratic constitution that will respect and affirm the rights of all citizens.

Nevertheless, and despite Prime Minister Erdogan’s acceptance speech yesterday in which he vowed to seek compromise on a new constitution, it is possible, even likely, that the AKP will promote its agenda with minimal compromise and consultation (as it has in the past). Such a unilateral approach increases the likelihood of the new constitution entrenching the illiberal practices evident in the AKP’s current exercise of power, including the targeting of journalists, libel suits, increased reliance on executive and administrative orders, enhanced cabinet powers at the expense of parliament, limited minority rights, and restrictions on freedom of association and civil society.

Turkish civil society is crucial to ensuring that Erdogan seeks compromise with the other three political parties that have entered parliament. In this context, civil society will prove just as key to saving Turkish democracy as it did during the optimistic years after the EU accepted Turkey’s application for membership in 1999 and major reforms started coming down the pipe. Support for strengthening political parties and institution building has been enormously successful, but further progress is unlikely without funding and empowering civil society to hold the government and political parties in check and goad them to respond to democratic demands.

A democratic regression in Turkey will not only mark the end of a regional success story but also set back Islamist/conservative democrats in other Muslim states who view the AKP as an exemplar. As recent survey research attests, 66% of Arabs view Turkey as a democratic model.

Turkish democracy is neither a mission accomplished nor a lost cause. Authoritarian trends can be reversed and the AKP government may yet return to the more liberal politics of its inception. However, this will take serious work and dedication from the government, opposition political parties, and civil society. These elections and upcoming plans to draft a new constitution provide at once a strong impetus for reform and a new starting point.

Sunday, June 12, 2011

Election Night . . .

From Radikal

Election results started to come out at six o'clock in the evening Turkey time, and it became evident early on that the AKP had a commanding lead of the popular vote. However, despite capturing a near 50% of voters, the largest percentage the party has captured since it first came to power in 2002, the party fell four seats shy of the 330 seats it needs in parliament (a 3/5 majority) to push through a constitution unilaterally. For an electoral map complete with official results, click here.

This means that for the first time in a long time the AKP will have to engage in political bargaining (see yesterday's post). Last year the AKP successfully pushed through a series of constitutional amendments using its previous 3/5 majority before successfully submitting the amendments to referendum. Meanwhile, the ultra-nationalist MHP managed to comfortably surpass the 10% threshold required for political parties to enter parliament, winning 13% of the popular vote. Though the party went from 69 to 54 seats, coming in above then 10% threshold made it difficult for the AKP to meet the 3/5 marker.

The AKP's chances at gaining a 3/5 majority were further damaged by the historical success of the Kurdish nationalist party, the BDP. The BDP managed to pick up a whopping 36 seats (up from 20), no doubt a result in part to growing disenchantment with -- and, in many cases, outright hostility toward -- the party in Turkey's mostly Kurdish southeast. Running as independents so as to escape the 10% threshold, the BDP captured 6% of the vote.

The AKP's nationalist turn, presumably an effort to win voters away from the MHP, had the predictable effect of alienating Kurdish voters. Ironically, as the only other political party competitive in the region, it also contributed greatly to its failure to win 3/5 of parliamenatary seats since the BDP fared so well. AKP's efforts to defeat the MHP were a gamble, losing Kurdish votes for ultra-nationalist votes (while at the same time empowering the BDP), and the party paid the price.

In addition to MHP votes, the party did pick up a significant number of votes from the SP (Felicity Party), a legacy of Erbakan's National Outlook movement, consolidating its control over the Islamist vote. It also picked up votes from the center-right Democrat Party, which also harkens back to an earlier era. I would venture to say these are the blocs that explain the party's ability to increase its share of the popular vote.

Meanwhile, the CHP, which took enormous risks this election cycle, performed under expectations. The CHP captured 26% of the popular vote to gain 38 seats (from 97 to 135), but some expected the party to poll over 30%. During the campaign, the CHP became by far the most progressive mainline party, taking positions more pro-European, pro-peace, and pro-liberal than the AKP (again, see yesterday's post). However, the party's controversial positions, especially on the Kurdish issue, may have alienated some in its formerly nationalist base -- votes that would have gone to the AKP or the MHP. However, nonetheless, CHP leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu and ""the new CHP" managed to gain almost 3.5 million new voters and pick up seats. Whether the CHP will continue to steer Kilicdaroglu's chart or be so frustrated with the results that it changes course once more remains to be seen.

In his acceptance speech, Prime Minister Erdogan vowed to build consensus on a new constitution and reiterated that he represented all Turkish citizens, not just those who voted for him. Prime Minister Erdogans aid the consensus would be built among political parties and civil society groups, all of which would be consulted during the process. However, the prime minister made the same promise last year and fell short.

All parties support drafting of a whole new document to replace the country's 1982 constitution drafted under military tutelage, but just what will happen in the coming months is very much up in the air. The AKP is far from weak, and could well gain the 3/5 majority it needs without too much maneuvering.

UPDATE I (6/13) -- For a truly wonderful electoral map complete with candidate names according to the provinces from which they were elected, click here. The AKP won more provinces along Turkey's more secular Western coast than it has in the past, but this should not be read as a significant setback for the CHP. Though the CHP no doubt lost votes in some of these Kemalist/nationalist strongholds, including majorities, it seems to have widened its support throughout the country, picking up votes in provinces where before it was not at all competitive.

Election results started to come out at six o'clock in the evening Turkey time, and it became evident early on that the AKP had a commanding lead of the popular vote. However, despite capturing a near 50% of voters, the largest percentage the party has captured since it first came to power in 2002, the party fell four seats shy of the 330 seats it needs in parliament (a 3/5 majority) to push through a constitution unilaterally. For an electoral map complete with official results, click here.

This means that for the first time in a long time the AKP will have to engage in political bargaining (see yesterday's post). Last year the AKP successfully pushed through a series of constitutional amendments using its previous 3/5 majority before successfully submitting the amendments to referendum. Meanwhile, the ultra-nationalist MHP managed to comfortably surpass the 10% threshold required for political parties to enter parliament, winning 13% of the popular vote. Though the party went from 69 to 54 seats, coming in above then 10% threshold made it difficult for the AKP to meet the 3/5 marker.

The AKP's chances at gaining a 3/5 majority were further damaged by the historical success of the Kurdish nationalist party, the BDP. The BDP managed to pick up a whopping 36 seats (up from 20), no doubt a result in part to growing disenchantment with -- and, in many cases, outright hostility toward -- the party in Turkey's mostly Kurdish southeast. Running as independents so as to escape the 10% threshold, the BDP captured 6% of the vote.

The AKP's nationalist turn, presumably an effort to win voters away from the MHP, had the predictable effect of alienating Kurdish voters. Ironically, as the only other political party competitive in the region, it also contributed greatly to its failure to win 3/5 of parliamenatary seats since the BDP fared so well. AKP's efforts to defeat the MHP were a gamble, losing Kurdish votes for ultra-nationalist votes (while at the same time empowering the BDP), and the party paid the price.

In addition to MHP votes, the party did pick up a significant number of votes from the SP (Felicity Party), a legacy of Erbakan's National Outlook movement, consolidating its control over the Islamist vote. It also picked up votes from the center-right Democrat Party, which also harkens back to an earlier era. I would venture to say these are the blocs that explain the party's ability to increase its share of the popular vote.

Meanwhile, the CHP, which took enormous risks this election cycle, performed under expectations. The CHP captured 26% of the popular vote to gain 38 seats (from 97 to 135), but some expected the party to poll over 30%. During the campaign, the CHP became by far the most progressive mainline party, taking positions more pro-European, pro-peace, and pro-liberal than the AKP (again, see yesterday's post). However, the party's controversial positions, especially on the Kurdish issue, may have alienated some in its formerly nationalist base -- votes that would have gone to the AKP or the MHP. However, nonetheless, CHP leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu and ""the new CHP" managed to gain almost 3.5 million new voters and pick up seats. Whether the CHP will continue to steer Kilicdaroglu's chart or be so frustrated with the results that it changes course once more remains to be seen.

In his acceptance speech, Prime Minister Erdogan vowed to build consensus on a new constitution and reiterated that he represented all Turkish citizens, not just those who voted for him. Prime Minister Erdogans aid the consensus would be built among political parties and civil society groups, all of which would be consulted during the process. However, the prime minister made the same promise last year and fell short.

All parties support drafting of a whole new document to replace the country's 1982 constitution drafted under military tutelage, but just what will happen in the coming months is very much up in the air. The AKP is far from weak, and could well gain the 3/5 majority it needs without too much maneuvering.

UPDATE I (6/13) -- For a truly wonderful electoral map complete with candidate names according to the provinces from which they were elected, click here. The AKP won more provinces along Turkey's more secular Western coast than it has in the past, but this should not be read as a significant setback for the CHP. Though the CHP no doubt lost votes in some of these Kemalist/nationalist strongholds, including majorities, it seems to have widened its support throughout the country, picking up votes in provinces where before it was not at all competitive.

Saturday, June 11, 2011

What Will Happen Tomorrow (And After)?

Reuters Photo from VOA Kurdish

I gave a radio interview this morning to Voice of America's Kurdish service in which I was asked what would be the impact of tomorrow's elections on the AKP-led government's plans to introduce a new constitution. Though the interview mostly focused on the Kurdish issue, of particular interest was just how successful the AKP could be in bringing forward plans to introduce a new constitution.

If the AKP wins at least 330 seats in the parliament (it now has 336), it will be able to introduce constitutional amendments without the need for much consensus before taking them to referendum -- an approach the AKP took last year and with great success. If the party manages to surpass 367 votes, it will have a 2/3 super majority that will allow it to unilaterally overhaul the constitution without the need for referendum. While the latter is unlikely and the former in doubt, the larger issue is just how sincere the party is in its reiterations that it will seek consensus as it moves forward. At the moment, all four parties with a chance of entering parliament have pledged to adopt a new constitution.

Last year, the party showed little concern as it pushed amendments rapidly forward. Neither civil society nor opposition political parties were given much voice in the process and the result was a referendum that basically polarized the Turkish public. The Kurdish nationalist BDP boycotted the referendum while the CHP and the MHP campaigned hard against the amendments. Though the official result was 58%, the actual number of Turkish citizens who approved the changes was lower given that a large number of Kurds who did boycott.

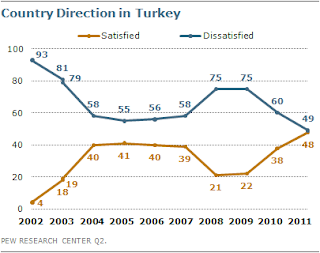

If the referendum is taken as a measure of the support for the AKP, it can be said that roughly over one-half of Turkish citizens approve of the party and the direction in which it is taking the country. This matches more or less with what a recent Pew poll found. According to the poll, 48 percent of Turkish citizens are satisfied with the direction the country is taking; however, 49 percent responded they are dissatisfied. The satisfied voters, more or less, can be assumed to be likely to vote for the AKP, but of more interest are those who are not. How many of these voters are simply typical Turkish cynics and how many are disenchanted with the party? The rising number of potentially disenchanted is cause for concern (and that is more than an understatement).

One of the most pressing problems in Turkish politics today is the amount of polarization in Turkish political society. Some of this can be explained by the increasing illiberal attitudes and policies of the AKP (see Tuesday's post), which, of course, is made all the more problematic by the AKP's seeming lack of willingness to engage opposition parties and craft serious political compromises when it comes to making government policy. Without an entrenched rights-based liberal democracy, the lack of compromise becomes all the more disturbing. A unilaterally-drawn up constitution will only serve to further polarize the Turkish public while continuing to fail at any real resolution of the classic dilemma posed by democracy and difference.

However, should the AKP fall short of 330 seats tomorrow, the party will be more inclined to compromise. Just exactly what this process of compromise would look like and what parties it would include remains to be seen, but perhaps for the first time in a long time the AKP will be forced to work with other parties to carve out a political agenda.

At stake are Erdogan's ambitions to institute a presidential system that would facilitate his ascendancy to the presidency. If Erdogan wins comfortably tomorrow, he will be more confident in these efforts. Even should the AKP fall short of gaining 3/5 of the seats in parliament, an increase in the popular vote for the AKP will embolden the already emboldened leader to move forward in his quest.

Meanwhile, just as interestingly, the CHP, which has drastically changed its leadership and party platform, will discover whether its new position in Turkish politics will be rewarded. The CHP is expected to pick up seats and increase its vote either way, but will likely have a difficult time gaining the 30% of the vote for which the party is striving. The CHP, which has billed itself as "the new CHP," has taken enormous risks this election cycle, presenting itself as pro-Europe, pro-liberal, pro-peace, and importantly, anti-nationalist and anti-coup. With Kilicdaroglu's victory over the party stalwart and former party secretary-general Onder Sav last year, the party has turned 180-degrees in many of its policies, especially in regard to the Kurds and its former pro-military/pro-coup attitude. Defeating Sav, Kilicdaroglu remarked, "The empire of fear is over in the CHP. Now it is time to end the empire of fear in Turkey."

The MHP will also face a serious test tomorrow. A little less than a month ago, there was serious question as to whether the ultra-nationalist party would be able to surpass the 10% threshold required to enter parliament. However, polls conducted at the end of June put the party safely over the threshold. That said, just how well the party does tomorrow will have an impact on the number of seats allocated to the AKP and CHP. The AKP has been competing for its nationalist voter base while the CHP's recent positions, especially in regard to the Kurds, might have alienated some in its former nationalist base to vote for the MHP.

And, finally, not without its own test will be the Kurdish nationalist BDP. The BDP currently has 20 seats in parliament, just enough to form a parliamentary group and be represented. However, there is little doubt that the BDP will surpass this number and could pick up well over 30 seats. Though the BDP candidates are running as independents since there in no chance they could meet the 10 percent threshold, the rising force of the party in the southeast and in Western cities populated by a large number of Kurdish migrants will indubitably be one of the most important stories of this election cycle. As its main challenger, the AKP's increased nationalist rhetoric is likely to work in favor of the party.

We'll see what tomorrow brings.

I gave a radio interview this morning to Voice of America's Kurdish service in which I was asked what would be the impact of tomorrow's elections on the AKP-led government's plans to introduce a new constitution. Though the interview mostly focused on the Kurdish issue, of particular interest was just how successful the AKP could be in bringing forward plans to introduce a new constitution.

If the AKP wins at least 330 seats in the parliament (it now has 336), it will be able to introduce constitutional amendments without the need for much consensus before taking them to referendum -- an approach the AKP took last year and with great success. If the party manages to surpass 367 votes, it will have a 2/3 super majority that will allow it to unilaterally overhaul the constitution without the need for referendum. While the latter is unlikely and the former in doubt, the larger issue is just how sincere the party is in its reiterations that it will seek consensus as it moves forward. At the moment, all four parties with a chance of entering parliament have pledged to adopt a new constitution.

Last year, the party showed little concern as it pushed amendments rapidly forward. Neither civil society nor opposition political parties were given much voice in the process and the result was a referendum that basically polarized the Turkish public. The Kurdish nationalist BDP boycotted the referendum while the CHP and the MHP campaigned hard against the amendments. Though the official result was 58%, the actual number of Turkish citizens who approved the changes was lower given that a large number of Kurds who did boycott.

If the referendum is taken as a measure of the support for the AKP, it can be said that roughly over one-half of Turkish citizens approve of the party and the direction in which it is taking the country. This matches more or less with what a recent Pew poll found. According to the poll, 48 percent of Turkish citizens are satisfied with the direction the country is taking; however, 49 percent responded they are dissatisfied. The satisfied voters, more or less, can be assumed to be likely to vote for the AKP, but of more interest are those who are not. How many of these voters are simply typical Turkish cynics and how many are disenchanted with the party? The rising number of potentially disenchanted is cause for concern (and that is more than an understatement).

One of the most pressing problems in Turkish politics today is the amount of polarization in Turkish political society. Some of this can be explained by the increasing illiberal attitudes and policies of the AKP (see Tuesday's post), which, of course, is made all the more problematic by the AKP's seeming lack of willingness to engage opposition parties and craft serious political compromises when it comes to making government policy. Without an entrenched rights-based liberal democracy, the lack of compromise becomes all the more disturbing. A unilaterally-drawn up constitution will only serve to further polarize the Turkish public while continuing to fail at any real resolution of the classic dilemma posed by democracy and difference.

However, should the AKP fall short of 330 seats tomorrow, the party will be more inclined to compromise. Just exactly what this process of compromise would look like and what parties it would include remains to be seen, but perhaps for the first time in a long time the AKP will be forced to work with other parties to carve out a political agenda.

At stake are Erdogan's ambitions to institute a presidential system that would facilitate his ascendancy to the presidency. If Erdogan wins comfortably tomorrow, he will be more confident in these efforts. Even should the AKP fall short of gaining 3/5 of the seats in parliament, an increase in the popular vote for the AKP will embolden the already emboldened leader to move forward in his quest.

Meanwhile, just as interestingly, the CHP, which has drastically changed its leadership and party platform, will discover whether its new position in Turkish politics will be rewarded. The CHP is expected to pick up seats and increase its vote either way, but will likely have a difficult time gaining the 30% of the vote for which the party is striving. The CHP, which has billed itself as "the new CHP," has taken enormous risks this election cycle, presenting itself as pro-Europe, pro-liberal, pro-peace, and importantly, anti-nationalist and anti-coup. With Kilicdaroglu's victory over the party stalwart and former party secretary-general Onder Sav last year, the party has turned 180-degrees in many of its policies, especially in regard to the Kurds and its former pro-military/pro-coup attitude. Defeating Sav, Kilicdaroglu remarked, "The empire of fear is over in the CHP. Now it is time to end the empire of fear in Turkey."

The MHP will also face a serious test tomorrow. A little less than a month ago, there was serious question as to whether the ultra-nationalist party would be able to surpass the 10% threshold required to enter parliament. However, polls conducted at the end of June put the party safely over the threshold. That said, just how well the party does tomorrow will have an impact on the number of seats allocated to the AKP and CHP. The AKP has been competing for its nationalist voter base while the CHP's recent positions, especially in regard to the Kurds, might have alienated some in its former nationalist base to vote for the MHP.

And, finally, not without its own test will be the Kurdish nationalist BDP. The BDP currently has 20 seats in parliament, just enough to form a parliamentary group and be represented. However, there is little doubt that the BDP will surpass this number and could pick up well over 30 seats. Though the BDP candidates are running as independents since there in no chance they could meet the 10 percent threshold, the rising force of the party in the southeast and in Western cities populated by a large number of Kurdish migrants will indubitably be one of the most important stories of this election cycle. As its main challenger, the AKP's increased nationalist rhetoric is likely to work in favor of the party.

We'll see what tomorrow brings.

Tuesday, June 7, 2011

Why Turkey and Turkish Civil Society Matter

Far too many Western political leaders, thinkers, and donors, especially here in Washington, have come to think of Turkish democracy as a “mission accomplished,” or at least, a project "near complete.” The sad state of affairs is indeed the opposite, and mostly sadly, it is this premature attitude that could turn Turkey back toward its authoritarian past rather than build on the democratic successes it has achieved in the past 15 years.

As American think-tanks bandy about a “Turkish model” as some ideal path for the newly emerging Arab democracies to follow, the real state of Turkish political affairs remains a mystery to all too many. In fact, Turkey now has more journalists in prison than any other country in the world, including China. And, like China, a new Internet regulation that goes into effect Aug. 22 will set up an online filtering and surveillance system by which every Turkish citizen will be followed by the government using an online profile. These developments are all the more disturbing given the ongoing Ergenekon investigation, which while supposed to bring down the infamous Turkish “deep state,” instead has been used as a political tool to go after the ruling AKP government’s political enemies.

Meanwhile, the Kurdish conflict, which the government’s “Kurdish opening” was to finally bring to a close by granting Turkey’s Kurdish population of 15 million plus people cultural and minority rights, has ground to a halt. Prime Minister Erdogan just over a year ago recognized the “Kurdish problem” as a democracy problem, but has since denied its existence. Last summer saw the largest escalation of the conflict since the 1990s, and given the government’s recent nationalist posturing, it is highly unlikely that the problem will be resolved.

Most important of all is Turkey’s stalled European Union accession process, the primary fuel behind the rapid-pace reforms that constitute Turkey’s democratic successes at the turn of the millennium. However, more than four years have passed since Turkey began accession negotiations, wherein the country has made little progress in fully meeting the EU’s Copenhagen criteria for democracy and human rights. Indeed, as Dilek Kurban notes in yesterday’s post, progress has actually become regression. Turkey now has a repressive Anti-Terrorism Law in place that has landed thousands in prison without adequate legal redress and torture, illegal detention, and impunity remain problems just as daunting as they were before the AKP entered power in 2002.

The main problem, more than any other, is a ruling party that has distanced itself from the liberal democracy it once embraced to in its place champion a majoritarian conception of rule by the people where minorities, opposition figures, and political dissenters are becoming less secure in their rights by the day. Democracy, as the AKP understands it, is rule by the majority—it is electoral authoritarianism dressed up to look nice for Western audiences keen to fondly fixate on the notion of an Islamist party that has somehow come to champion a long oppressed majority while adopting liberal values. However, the AKP is not liberal. While there is plenty of truth that the majority of conservative Muslim Anatolia has been repressed throughout the history of the country’s history, now it is the majority who is comfortable to reign over the minority.

There is no resolving the Madisonian dilemma—the inherent conflict between majority rule and individual liberties—for the ruling AKP government. There is only a will to power—a will evinced by Prime Minister Erdogan’s designs to create a presidential system. As The Economist noted in its controversial editorial endorsing the CHP and which now has the prime minister fuming about Zionist-driven conspiracies, if the AKP is to unilaterally push through a new constitution, it could end up being worse than the greatly amended one currently in place.

Ironically, if the United States and Europe do not move fast to realize what is happening inside Turkey, the world will lose a country that really could serve as a democratic example to the Arab Middle East. The AKP government made tremendous progress when it first came to power in 2002, and it could be said that the party’s first years in office provided the best government in the history of the Turkish Republic. However, a lot has happened since and the model is at risk. If Turkey’s democratic progress is ultimately lost, then there will not only be the lack of a democratic success story in the region but a failure that could set back Islamist/conservative democrats in other Muslim countries who otherwise have good chances of making democracy work. And, as recent survey research attests, Arabs are paying attention. (66% of Arabs surveyed at the end of last summer said they viewed Turkey as a democratic model.)

What is to be done?

Now is the time for action. The EU accession engine that powered the AKP’s early reform efforts is imperiled by the Greek Cypriot presidency, which will commence in just a little more than a year from now. This means the Turkish government, which will still be led by the AKP whether the party gains a super majority or not, must make serious progress toward accession. The country is in a race against time. And, no matter what happens in June elections, movement toward a new constitution, or at least major constitutional reform, will be on the plate.

In this context, Turkish civil society will prove key to saving Turkish democracy just as it did during the optimistic years after the EU accepted Turkey’s application for membership in 1999 and major reforms started coming down the pipe. The authoritarian tendencies of Turkish political parties, not exclusive to the current party in power, need to be countered by civil society.

When the AKP tried to make adultery illegal in 2004 and ignore legislative proposals that would reduce the sentences for honor killings and rape in certain instances, it was a highly mobilized network of women’s groups that pushed the party to do the right thing. Many of these groups had become empowered thanks to donor money and expertise, and they fought the good fight, and well, won.

Though Turkey is now confronting a different set of challenges, support for civil society is just as critical now as it was then to support these groups. And, what kind of support exactly? What is needed are not requests for proposals that nearly prompt groups to apply for money, but rather funds for genuine projects grown out of grassroots understandings of political expediency. Turkish civil society groups should be encouraged to do more to work together, as women’s groups did in 2004, and even more importantly, engage political parties, the government, and the state (listed here in an ascending order of difficulty).

Support for strengthening political parties and institution-building has been enormously successful in Turkey, and to some extent, has resulted in the recent democratic turn by CHP we have seen of late, but without funding civil society to keep political parties in check and goad them to respond to democratic demands, little will get done.

And, the impact?

The AKP has accomplished tremendous feats in its time in power, but the party has grown too strong while civil society has lagged behind. Now confident that it is the voice of the majority, without an active, challenging, forward-looking civil society to remind it of its earlier liberal promises, the party will be doomed to failure—and, with it, Turkish democracy. It is no coincidence that civil society and liberalism emerged together in the history of other countries’ political development, and the two go together in Turkey as well.

If Turkish civil society, adequately funded and attended to, can take the mass protest movements we have seen in response to the government’s plans to pass draconian restrictions on Internet usage and round-up journalists and actually organize this anomic political mobilization into smart, organic political engagement with politicians, the result would prove not only beneficial to the longevity of Turkish democracy but also serve as an example to the Arab world.

As American think-tanks bandy about a “Turkish model” as some ideal path for the newly emerging Arab democracies to follow, the real state of Turkish political affairs remains a mystery to all too many. In fact, Turkey now has more journalists in prison than any other country in the world, including China. And, like China, a new Internet regulation that goes into effect Aug. 22 will set up an online filtering and surveillance system by which every Turkish citizen will be followed by the government using an online profile. These developments are all the more disturbing given the ongoing Ergenekon investigation, which while supposed to bring down the infamous Turkish “deep state,” instead has been used as a political tool to go after the ruling AKP government’s political enemies.

Meanwhile, the Kurdish conflict, which the government’s “Kurdish opening” was to finally bring to a close by granting Turkey’s Kurdish population of 15 million plus people cultural and minority rights, has ground to a halt. Prime Minister Erdogan just over a year ago recognized the “Kurdish problem” as a democracy problem, but has since denied its existence. Last summer saw the largest escalation of the conflict since the 1990s, and given the government’s recent nationalist posturing, it is highly unlikely that the problem will be resolved.

Most important of all is Turkey’s stalled European Union accession process, the primary fuel behind the rapid-pace reforms that constitute Turkey’s democratic successes at the turn of the millennium. However, more than four years have passed since Turkey began accession negotiations, wherein the country has made little progress in fully meeting the EU’s Copenhagen criteria for democracy and human rights. Indeed, as Dilek Kurban notes in yesterday’s post, progress has actually become regression. Turkey now has a repressive Anti-Terrorism Law in place that has landed thousands in prison without adequate legal redress and torture, illegal detention, and impunity remain problems just as daunting as they were before the AKP entered power in 2002.

The main problem, more than any other, is a ruling party that has distanced itself from the liberal democracy it once embraced to in its place champion a majoritarian conception of rule by the people where minorities, opposition figures, and political dissenters are becoming less secure in their rights by the day. Democracy, as the AKP understands it, is rule by the majority—it is electoral authoritarianism dressed up to look nice for Western audiences keen to fondly fixate on the notion of an Islamist party that has somehow come to champion a long oppressed majority while adopting liberal values. However, the AKP is not liberal. While there is plenty of truth that the majority of conservative Muslim Anatolia has been repressed throughout the history of the country’s history, now it is the majority who is comfortable to reign over the minority.

There is no resolving the Madisonian dilemma—the inherent conflict between majority rule and individual liberties—for the ruling AKP government. There is only a will to power—a will evinced by Prime Minister Erdogan’s designs to create a presidential system. As The Economist noted in its controversial editorial endorsing the CHP and which now has the prime minister fuming about Zionist-driven conspiracies, if the AKP is to unilaterally push through a new constitution, it could end up being worse than the greatly amended one currently in place.

Ironically, if the United States and Europe do not move fast to realize what is happening inside Turkey, the world will lose a country that really could serve as a democratic example to the Arab Middle East. The AKP government made tremendous progress when it first came to power in 2002, and it could be said that the party’s first years in office provided the best government in the history of the Turkish Republic. However, a lot has happened since and the model is at risk. If Turkey’s democratic progress is ultimately lost, then there will not only be the lack of a democratic success story in the region but a failure that could set back Islamist/conservative democrats in other Muslim countries who otherwise have good chances of making democracy work. And, as recent survey research attests, Arabs are paying attention. (66% of Arabs surveyed at the end of last summer said they viewed Turkey as a democratic model.)

What is to be done?

Now is the time for action. The EU accession engine that powered the AKP’s early reform efforts is imperiled by the Greek Cypriot presidency, which will commence in just a little more than a year from now. This means the Turkish government, which will still be led by the AKP whether the party gains a super majority or not, must make serious progress toward accession. The country is in a race against time. And, no matter what happens in June elections, movement toward a new constitution, or at least major constitutional reform, will be on the plate.

In this context, Turkish civil society will prove key to saving Turkish democracy just as it did during the optimistic years after the EU accepted Turkey’s application for membership in 1999 and major reforms started coming down the pipe. The authoritarian tendencies of Turkish political parties, not exclusive to the current party in power, need to be countered by civil society.

When the AKP tried to make adultery illegal in 2004 and ignore legislative proposals that would reduce the sentences for honor killings and rape in certain instances, it was a highly mobilized network of women’s groups that pushed the party to do the right thing. Many of these groups had become empowered thanks to donor money and expertise, and they fought the good fight, and well, won.

Though Turkey is now confronting a different set of challenges, support for civil society is just as critical now as it was then to support these groups. And, what kind of support exactly? What is needed are not requests for proposals that nearly prompt groups to apply for money, but rather funds for genuine projects grown out of grassroots understandings of political expediency. Turkish civil society groups should be encouraged to do more to work together, as women’s groups did in 2004, and even more importantly, engage political parties, the government, and the state (listed here in an ascending order of difficulty).

Support for strengthening political parties and institution-building has been enormously successful in Turkey, and to some extent, has resulted in the recent democratic turn by CHP we have seen of late, but without funding civil society to keep political parties in check and goad them to respond to democratic demands, little will get done.

And, the impact?

The AKP has accomplished tremendous feats in its time in power, but the party has grown too strong while civil society has lagged behind. Now confident that it is the voice of the majority, without an active, challenging, forward-looking civil society to remind it of its earlier liberal promises, the party will be doomed to failure—and, with it, Turkish democracy. It is no coincidence that civil society and liberalism emerged together in the history of other countries’ political development, and the two go together in Turkey as well.

If Turkish civil society, adequately funded and attended to, can take the mass protest movements we have seen in response to the government’s plans to pass draconian restrictions on Internet usage and round-up journalists and actually organize this anomic political mobilization into smart, organic political engagement with politicians, the result would prove not only beneficial to the longevity of Turkish democracy but also serve as an example to the Arab world.

Wednesday, June 1, 2011

Everyone is a Turkish Citizen

PHOTO from Taraf

The CHP has declared its support to amend the constitution in favor of a non-ethnic understanding of Turkish citizenship. Under the country's current constitution (drafted under military tutelage) all citizens of Turkey are members of the Turkish nation (click here, in Turkish). Further, according to Article 66, every Turkish citizen is considered to be a Turk. This is the first time that any major Turkish political party in the entire history of the Turkish republic has offered such a non-ethnic understanding of citizenship.

The change is proposed as part of a wide series of concrete constitutional reforms the CHP has endeavored to put forward. The proposed reforms were drafted by CHP vice-president Suheyl Batum with a team of 35 academics. Though some have speculated that the CHP is too diverse a coalition to generate concrete proposals (Batum himself hales from the center-right), the constitutional proposals are more solid in substantive than the rhetoric coming out of the AKP.

The CHP has also expressed its support for education in mother tongue, which requires amending Article 42, which stipulates that no Turkish citizen can receive education in any mother tongue language other than Turkish. Article 42 specifically targets languages native to Anatolia, such as Kurdish, while allowing for education in English, French, and other foreign languages.

Kilicdaroglu addressing a campaign rally in Hakkari. PHOTO from Milliyet

Meanwhile, for the first time in nine years, the CHP held an election rally in Diyarbakir a day ahead of the rally AKP is expecting to hold tomorrow. Though turnout was somewhat disappointing for the party (only ~2,000 people showed up), it is clear the CHP is performing a series of firsts that could find itself winning voters in the southeast and currying favor with liberal reformers who have since become disenchanted by the AKP.

For an accounting and history, as well as some more context, of the proposals the CHP is putting forward on the Kurdish issue, see this post from a few weeks ago.

Prime Minister Erdogan will hold a rally in Diyarbakir today.

The CHP has declared its support to amend the constitution in favor of a non-ethnic understanding of Turkish citizenship. Under the country's current constitution (drafted under military tutelage) all citizens of Turkey are members of the Turkish nation (click here, in Turkish). Further, according to Article 66, every Turkish citizen is considered to be a Turk. This is the first time that any major Turkish political party in the entire history of the Turkish republic has offered such a non-ethnic understanding of citizenship.

The change is proposed as part of a wide series of concrete constitutional reforms the CHP has endeavored to put forward. The proposed reforms were drafted by CHP vice-president Suheyl Batum with a team of 35 academics. Though some have speculated that the CHP is too diverse a coalition to generate concrete proposals (Batum himself hales from the center-right), the constitutional proposals are more solid in substantive than the rhetoric coming out of the AKP.

The CHP has also expressed its support for education in mother tongue, which requires amending Article 42, which stipulates that no Turkish citizen can receive education in any mother tongue language other than Turkish. Article 42 specifically targets languages native to Anatolia, such as Kurdish, while allowing for education in English, French, and other foreign languages.

Kilicdaroglu addressing a campaign rally in Hakkari. PHOTO from Milliyet

Meanwhile, for the first time in nine years, the CHP held an election rally in Diyarbakir a day ahead of the rally AKP is expecting to hold tomorrow. Though turnout was somewhat disappointing for the party (only ~2,000 people showed up), it is clear the CHP is performing a series of firsts that could find itself winning voters in the southeast and currying favor with liberal reformers who have since become disenchanted by the AKP.

For an accounting and history, as well as some more context, of the proposals the CHP is putting forward on the Kurdish issue, see this post from a few weeks ago.

Prime Minister Erdogan will hold a rally in Diyarbakir today.

Friday, April 15, 2011

Trust Not the People

Aengus Collins wrote an excellent piece last fall on the democratic flaws inherent in Turkey's current system of closed-list proportional representation. As Collins notes, though the 10% threshold required of parties to enter parliament gets most of the attention (including recent mention in a 2010 Council of Europe report), considerable less attention is paid to the actual method by which parties and voters choose candidates. From Collins:

Prime Minister Erdogan has announced plans to draft a new constitution after the June 12 election, including a move to a presidential system. Why not an open-party list in addition?

Aengus also gives attention to parliamentary immunity, referencing Simon Wigley's equally cogent 2009 HRQ article on the topic. That one is also well worth the read.

There are problems at every stage of Turkey’s electoral process. As I highlighted in my most recent post, parliament’s 550 seats are badly misallocated among the country’s 81 provinces. Next, the processes used to translate individual votes into seats for parties are deeply skewed. The 10 per cent threshold that parties need to clear before they can enter parliament deservedly gets the most attention, but it’s not the only issue here. Once the threshold has been passed, the d’Hondt method is used to distribute seats among the remaining parties. Of the many variants of proportional representation, d’Hondt is the least proportional, systematically favouring larger parties.*Electoral systems are not the sexiest of business, but do not get enough attention. One of Turkey's chronic problems is the sheer strength that political parties wield over the system. Political leaders in Turkey are famed for staying around forever: once you are at the top of your party, there is little going away. This is, of course, also a problem of internal party democracy, but once leaders ascend to the position of party leader, they can virtually choose who will and will not be elected. Of course, this creates plenty of incentive for corruption, weak candidates with little popular appeal (think Deniz Baykal), and most importantly, a low level of democratic responsiveness to the people. The whole piece is worth a thorough read, and kudos to Aengus for writing it.

We reach a further set of problems when it comes to filling the seats that have been allocated to the various parties. Turkey uses a closed-list proportional representation system. This means that voters vote for the party of their choice, but there is no mechanism for them to express a preference for one or more of the party’s individual candidates. Instead, a list of candidates for each province is drawn up by the party leadership and any seats won in that province are automatically assigned to the names on the list, starting from the top.

It’s not the list per se that causes the problems here. List-based proportional representation is an extremely widely used electoral approach. But in most cases an open list is used, which allows voters to influence the rank-order of the names on the list, and therefore the order in which seats will be allocated to party candidates. Turkey’s closed-list variant is less common. It has tended to feature in countries where democracy is relatively novel and/or shallow. The reasons for this should be clear. Closed lists produce an authoritarianism-friendly form of democracy, keeping power and control in the hands of party elites rather than individual voters.