PHOTO from Hurriyet Daily News

At a time when Turkey is gearing up to craft a new constitution, its parliament is currently drafting changes to its rules that would significantly shorten the period of debate, extend sessions into the weekend if necessary, and limit proposals to draft laws.

The ruling AKP is claiming the rules are intended to streamline debate and increase parliamentary efficiency while opposition parties are claiming the new regulations are intended to silence opposition voices (for specific changes, click here). The debate reached a climax yesterday when the CHP, the largest opposition party, stormed the rostrum after Speaker Cemil Cicek closed debate after a five hour standoff wherein CHP and BDP lawmakers shouted slogans against the speaker, forcing Cicek to call numerous recesses.

The eventual result was a fistfight after Cicek closed the session. Fistfights are not altogether uncommon in the parliament, and in 2001, a similar debate over rules left one parliamentarian dead of a heart attack after a fight broke out. Cicek has been trying for the past week to reach a compromise between the AKP and opposition parties, though his efforts have clearly failed.

All three opposition parties are united against the rules changes, and claim the AKP is attempting to fix the rules ahead of the constitutional draft being submitted to the general assembly in order to easily force the document out of parliament and submit it to referendum, as the party did the 2010 amendment package. Though the AKP is three votes shy of the 330 votes (3/5 majority) it needs to pass the new constitution in parliament and take it to referendum (as it did in 2010), the opposition fears that the AKP could well cobble together this majority rather than engage all parties in a more consensual process.

Clearly such an endeavor would hurt the legitimacy of a new constitution and certainly contradict the ruling party's stated objective of achieving the widest degree of consensus possible -- but, here again, the operative word is "possible," and efforts to build consensus will depend on just how the AKP interprets this mission, and how committed it will remain to it. A party operating with a solid 3/5 majority since its entrance to parliament in 2002, consensus-building has not exactly been the party's forté, nor has it, in all fairness, to any Turkish political party. For more on this point, see E. Fuat Keyman and Meltem Muftuler-Bac's recent article in the January issue of the Journal of Democracy.

The appropriateness of fist-fighting aside, the move to change the rules has led opposition parties to boycott the constitutional reconciliattion commission charged with framing a new civilian constitution, and has, in general, detracted from the commission's task-at-hand. The commission is comprised of 12 members (three from every party) and is designed to garner consensus among political parties and civil society.

At this phase of the re-drafting process, the commission is currently seeking proposals from politicians and civil society groups, which up until recently, could be viewed publicly on this website parliament setup in October. Yet at the beginning of February the commission decided to hide the substance of proposals being submitted in order to protect the names of individuals and groups submitting them since some were quite controversial. At the moment, only the names of individuals and groups submitting proposals are left on the site. For more, see this front-page article from the Jan. 27 edition of Milliyet.

Showing posts with label MHP. Show all posts

Showing posts with label MHP. Show all posts

Friday, February 10, 2012

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

Rough Waters Ahead?

PHOTO from Radikal

Sunday's elections created what is perhaps the most representative parliament in the history of the Turkish Republic. Of the 87% of eligible Turkish voters who showed up to cast ballots, only 4.4% voted for parties were not ultimately elected to parliament. This is down from 13% in 2007 and 32% in 2002. This representation problem has been a function of small political parties being unable to meet the country's high 10% threshold required to enter parliament. (The Kurdish BDP is an exception to this rule since it has not run as a political party, but rather chosen to run candidates as independents. A difficult feat to pull off, the BDP won 36 MPs this parliamentary election cycle.)

However, though there are now few political parties in parliament, this does not mean Turkey is necessarily any less divided. In fact, each of the four political parties now represented have unique constituencies and platforms that do not necessarily square with each other or facilitate compromise. As the AKP vows to seek compromise and civil society input as it moves forward with re-drafting the country's 1982 constitution, which was drafted in the shadow of a dramatic coup in 1980, it is unclear just how successful it can and will be.

Assessing the BDP

Cengiz Candar argues in today's Radikal that what a " BDP opening" is needed, meaning that the AKP must accommodate the voices and politics of the Kurdish nationalist party. At the same time, Candar, who is joined by other liberal public intellectuals who support Kurdish political, civil, and cultural rights, argues that the BDP has not shown itself to be a positive player when it comes to adopting the conciliatory politics required to reach a solution to the age-old Kurdish problem.

As Henri Barkey elucidated at an event at the Carnegie Endowment today (podcast here), the BDP's victory is impressive in that it resulted not only from the support it receives in the southeast (and in Kurdish areas throughout the country), but also from its tremendous capacity to organize. Successfully unning independent candidates for parliament is no easy task, and basically required the party to apportion its support for specific candidates running at the provincial level and then organize voters to elect these candidates. For example, in Diyarbakir, where support for the BDP was high, BDP supporters were divided between the number of candidates the BDP thought it could successfully run. Such a strategy requires the BDP to perform a complicated electoral math in determining just how many candidates it can elect in the context of a complicated electoral system and successfully rally the vote behind these independent candidates.

Though the BDP's success should not be underestimated, it should also not be overplayed. As Candar explains, though the BDP has gotten better at electoral engineering, political support for the party has not necessarily increased. Further, it should not be forgotten that a significant number of Kurds voted for the AKP despite its heavy nationalist rhetoric (Candar estimates 42%). Had the AKP not run a nationalist campaign in an effort to run the MHP into the ground, the result might have been different. Candar also points attention to the factions the BDP has managed to bring together (for example, bringing leftists together with staunch Kurdish nationalists and pro-Kurdish conservatives like Altan Tan and Sereafettin Elci). According to Candar, though this coalition-building is taking place at the elite level, the BDP has not succeeded in doing so among voters.

Trouble Brewing

In the days after the election, the BDP used this mammoth victory to call for the release of PKK terrorist leader Abdullah Ocalan and direct negotiations with the PKK, actions sure to infuriate the vast majority of Turkish votes. In doing, the BDP is alienating itself from the larger electorate and adopting a divisive politics sure to further fuel the conflict.

At the same time, the AKP has paid little attention to the Kurdish problem, the existence of which the party denied during the campaign, and is instead focusing on moving onward with business as usual. The two positions combined create the conditions for a political crisis, which could come soon given that six of BDP's deputies are currently in jail and their eligibility to hold seats in parliament still up in the air.

Chief among these is Hatip Dicle, who was convicted in 2009 for disseminating PKK propaganda and whose candidacy was at the heart of the riots that enfolded at the end of April when the High Election Board (YSK) invalidated the candidacies of 11 BDP candidates (see April 21 post). On June 9, just three days before the elections, the Supreme Court of Appeals upheld Dicle's conviction. Though it was too late to remove his name from the ballot, the High Elections Board will decide whether he is able to serve in parliament.

The six BDP candidates currently jailed as part of the KCK operations (and who are awaiting trial) include Gulseren Yildirm, Ibrahim Ayhan, Selma Irmak, Faysal Sarayildiz, Kemal Aktas, and Dicle. Dicle's case is special since he is not only jailed and awaiting trial for alleged membership in the PKK (KCK), but has been convicted previously and been unable to attain the necessary paperwork required to allow him to enter parliament. The Constitution bars convicted persons from holding parliamentary office. (In addition to the six jailed BDP candidates, two CHP candidates and one MHP candidate, both recently elected, are also currently detained (for their role in Ergenekon).)

Meeting in Diyarbakir yesterday, the BDP called for the release of all six elected members and demanded the release of Ocalan. If the release of the six was not controversial enough, combining such a move with Ocalan's release is not politically savvy nor helpful for the peace process. Reaction in the Turkish press, nationalist and otherwise, has been harsh, and will likely only increase in intensity should a crisis with Dicle come to a head.

Will the AKP Seek Compromise?

Speculation is still high as to whether Prime Minister Erdogan will seek a presidential term in either 2012 or 2014 given the party's successful election result. While some observers argues the party's loss of seats and new need for compromise when it comes to amending the country's constitution renders null the possibility of a powerful Erdogan presidency, others conjecture the AKP will still be able to find the support it needs to change the constitution and empower Erdogan.

The prime minister has announced that he will not run for parliament again, and the AKP's current by-laws prevent him from being appointed to another term as prime minister. CSIS' Bulent Aliriza writes

Again, a key question here is whether and how the party will attempt to repair the bridges it has burnt with the large number of Kurdish voters to whom the party turned its back. Though the AKP failed to push the ultra-nationalist MHP beneath the 10% threshold, according to Barkey, any increase in the AKP's number of voters (above the 50% of the country who supported it in this election) will come from nationalist voters.

Getting these votes is dependent on how the party treats the Kurdish issue, and should it be intent to continue its nationalist rhetoric, the BDP opening for which Candar hopes is simply not going to come to fruition. At the same time, the AKP has expressed intent to negotiate with the CHP and the MHP, and there are those in the party who realize the necessity of dealing with the BDP, however unsavory and threatening its politics. At the party's parliamentary group meeting today, Erdogan re-affirmed his intent to move forward with the constitution and said he would personally supervise negotiations with the opposition and engagement with civil society.

Just how all of this will happen is yet to be seen, especially given that the next few weeks could prove difficult if the courts and the YSK prevent the release and entry of those elected candidates currently jailed. And, while Turkey might have a more representative parliament, a less divided country it is not.

Sunday's elections created what is perhaps the most representative parliament in the history of the Turkish Republic. Of the 87% of eligible Turkish voters who showed up to cast ballots, only 4.4% voted for parties were not ultimately elected to parliament. This is down from 13% in 2007 and 32% in 2002. This representation problem has been a function of small political parties being unable to meet the country's high 10% threshold required to enter parliament. (The Kurdish BDP is an exception to this rule since it has not run as a political party, but rather chosen to run candidates as independents. A difficult feat to pull off, the BDP won 36 MPs this parliamentary election cycle.)

However, though there are now few political parties in parliament, this does not mean Turkey is necessarily any less divided. In fact, each of the four political parties now represented have unique constituencies and platforms that do not necessarily square with each other or facilitate compromise. As the AKP vows to seek compromise and civil society input as it moves forward with re-drafting the country's 1982 constitution, which was drafted in the shadow of a dramatic coup in 1980, it is unclear just how successful it can and will be.

Assessing the BDP

Cengiz Candar argues in today's Radikal that what a " BDP opening" is needed, meaning that the AKP must accommodate the voices and politics of the Kurdish nationalist party. At the same time, Candar, who is joined by other liberal public intellectuals who support Kurdish political, civil, and cultural rights, argues that the BDP has not shown itself to be a positive player when it comes to adopting the conciliatory politics required to reach a solution to the age-old Kurdish problem.

As Henri Barkey elucidated at an event at the Carnegie Endowment today (podcast here), the BDP's victory is impressive in that it resulted not only from the support it receives in the southeast (and in Kurdish areas throughout the country), but also from its tremendous capacity to organize. Successfully unning independent candidates for parliament is no easy task, and basically required the party to apportion its support for specific candidates running at the provincial level and then organize voters to elect these candidates. For example, in Diyarbakir, where support for the BDP was high, BDP supporters were divided between the number of candidates the BDP thought it could successfully run. Such a strategy requires the BDP to perform a complicated electoral math in determining just how many candidates it can elect in the context of a complicated electoral system and successfully rally the vote behind these independent candidates.

Though the BDP's success should not be underestimated, it should also not be overplayed. As Candar explains, though the BDP has gotten better at electoral engineering, political support for the party has not necessarily increased. Further, it should not be forgotten that a significant number of Kurds voted for the AKP despite its heavy nationalist rhetoric (Candar estimates 42%). Had the AKP not run a nationalist campaign in an effort to run the MHP into the ground, the result might have been different. Candar also points attention to the factions the BDP has managed to bring together (for example, bringing leftists together with staunch Kurdish nationalists and pro-Kurdish conservatives like Altan Tan and Sereafettin Elci). According to Candar, though this coalition-building is taking place at the elite level, the BDP has not succeeded in doing so among voters.

Trouble Brewing

In the days after the election, the BDP used this mammoth victory to call for the release of PKK terrorist leader Abdullah Ocalan and direct negotiations with the PKK, actions sure to infuriate the vast majority of Turkish votes. In doing, the BDP is alienating itself from the larger electorate and adopting a divisive politics sure to further fuel the conflict.

At the same time, the AKP has paid little attention to the Kurdish problem, the existence of which the party denied during the campaign, and is instead focusing on moving onward with business as usual. The two positions combined create the conditions for a political crisis, which could come soon given that six of BDP's deputies are currently in jail and their eligibility to hold seats in parliament still up in the air.

Chief among these is Hatip Dicle, who was convicted in 2009 for disseminating PKK propaganda and whose candidacy was at the heart of the riots that enfolded at the end of April when the High Election Board (YSK) invalidated the candidacies of 11 BDP candidates (see April 21 post). On June 9, just three days before the elections, the Supreme Court of Appeals upheld Dicle's conviction. Though it was too late to remove his name from the ballot, the High Elections Board will decide whether he is able to serve in parliament.

The six BDP candidates currently jailed as part of the KCK operations (and who are awaiting trial) include Gulseren Yildirm, Ibrahim Ayhan, Selma Irmak, Faysal Sarayildiz, Kemal Aktas, and Dicle. Dicle's case is special since he is not only jailed and awaiting trial for alleged membership in the PKK (KCK), but has been convicted previously and been unable to attain the necessary paperwork required to allow him to enter parliament. The Constitution bars convicted persons from holding parliamentary office. (In addition to the six jailed BDP candidates, two CHP candidates and one MHP candidate, both recently elected, are also currently detained (for their role in Ergenekon).)

Meeting in Diyarbakir yesterday, the BDP called for the release of all six elected members and demanded the release of Ocalan. If the release of the six was not controversial enough, combining such a move with Ocalan's release is not politically savvy nor helpful for the peace process. Reaction in the Turkish press, nationalist and otherwise, has been harsh, and will likely only increase in intensity should a crisis with Dicle come to a head.

Will the AKP Seek Compromise?

Speculation is still high as to whether Prime Minister Erdogan will seek a presidential term in either 2012 or 2014 given the party's successful election result. While some observers argues the party's loss of seats and new need for compromise when it comes to amending the country's constitution renders null the possibility of a powerful Erdogan presidency, others conjecture the AKP will still be able to find the support it needs to change the constitution and empower Erdogan.

The prime minister has announced that he will not run for parliament again, and the AKP's current by-laws prevent him from being appointed to another term as prime minister. CSIS' Bulent Aliriza writes

The new constitution seems certain to usher in a presidential system, and it is clear that Erdogan intends to run for the presidency, either in 2012 or more likely in 2014. If he were to choose the latter date, he would then be in a position to implement his “Target 2023” election manifesto through the centennial of the Turkish Republic as president. However, the inability of the JDP to obtain 330 seats, which would have enabled Erdogan to get public approval for a new constitution in a referendum, presents an obstacle that needs to be overcome.Apart from the question of Erdogan continuance as the leading force in Turkish politics, the more immediate question is whether and just how the AKP will seek compromise and consensus on the constitution, especially given the likelihood of conflict over the jailed opposition candidates who have just been elected from parliament.

Again, a key question here is whether and how the party will attempt to repair the bridges it has burnt with the large number of Kurdish voters to whom the party turned its back. Though the AKP failed to push the ultra-nationalist MHP beneath the 10% threshold, according to Barkey, any increase in the AKP's number of voters (above the 50% of the country who supported it in this election) will come from nationalist voters.

Getting these votes is dependent on how the party treats the Kurdish issue, and should it be intent to continue its nationalist rhetoric, the BDP opening for which Candar hopes is simply not going to come to fruition. At the same time, the AKP has expressed intent to negotiate with the CHP and the MHP, and there are those in the party who realize the necessity of dealing with the BDP, however unsavory and threatening its politics. At the party's parliamentary group meeting today, Erdogan re-affirmed his intent to move forward with the constitution and said he would personally supervise negotiations with the opposition and engagement with civil society.

Just how all of this will happen is yet to be seen, especially given that the next few weeks could prove difficult if the courts and the YSK prevent the release and entry of those elected candidates currently jailed. And, while Turkey might have a more representative parliament, a less divided country it is not.

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

A Pyrhhic Victory?

I recently wrote a short entry on the elections for Democracy Digest, a project of the National Endowment for Democracy. An excerpt:

Increasingly, Turkey is polarized between those who support the AKP and those who do not. The AKP’s critics include not only the secular elite, but also liberals, Kurds and other minority groups, and others who fear the intolerance with which the party deals with difference and dissent.For the full entry, click here. The blog is a good way to monitor political development throughout the world.

However, the new parliament presents fresh opportunities for compromise and reconciliation. All parties agree that Turkey should adopt a new constitution, and given the CHP’s progressive turn, the country now has a genuine opportunity to pass a liberal democratic constitution that will respect and affirm the rights of all citizens.

Nevertheless, and despite Prime Minister Erdogan’s acceptance speech yesterday in which he vowed to seek compromise on a new constitution, it is possible, even likely, that the AKP will promote its agenda with minimal compromise and consultation (as it has in the past). Such a unilateral approach increases the likelihood of the new constitution entrenching the illiberal practices evident in the AKP’s current exercise of power, including the targeting of journalists, libel suits, increased reliance on executive and administrative orders, enhanced cabinet powers at the expense of parliament, limited minority rights, and restrictions on freedom of association and civil society.

Turkish civil society is crucial to ensuring that Erdogan seeks compromise with the other three political parties that have entered parliament. In this context, civil society will prove just as key to saving Turkish democracy as it did during the optimistic years after the EU accepted Turkey’s application for membership in 1999 and major reforms started coming down the pipe. Support for strengthening political parties and institution building has been enormously successful, but further progress is unlikely without funding and empowering civil society to hold the government and political parties in check and goad them to respond to democratic demands.

A democratic regression in Turkey will not only mark the end of a regional success story but also set back Islamist/conservative democrats in other Muslim states who view the AKP as an exemplar. As recent survey research attests, 66% of Arabs view Turkey as a democratic model.

Turkish democracy is neither a mission accomplished nor a lost cause. Authoritarian trends can be reversed and the AKP government may yet return to the more liberal politics of its inception. However, this will take serious work and dedication from the government, opposition political parties, and civil society. These elections and upcoming plans to draft a new constitution provide at once a strong impetus for reform and a new starting point.

Monday, June 13, 2011

A Country Divided

Cartoon from Hurriyet

Sounding the same refrain as last September's constitutional referendum, yesterday's election results reveal Turkey to be increasingly divided between those who support the ruling AKP government and those who do not.

Yesterday the AKP managed to increase its vote from the 46.58% it captured in 2007 parliamentary elections to 49.91%, though the party lost lost seats and its 3/5 majority in parliament (see yesterday's post).

Additionally, the AKP became the first party since the Democratic Party in the 1950s to win three consecutive parliamentary elections; however, unlike the Democratic Party, the AKP has become more popular each election, not less. Yet, while the results hint at the AKP's growing popularity, they also hint at a growing disconnect between the party's supporters and those who fear its burgeoning illiberal tendencies (see last Tuesday's post).

The Other Half

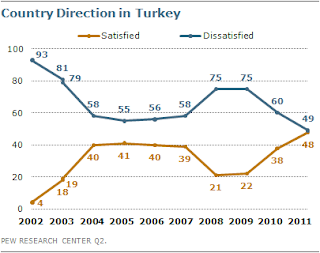

As echoed by the results of a recent Pew poll, Turkey is becoming an increasingly divided country. While those who support the AKP continue to enthusiastically return it to power, the other half (and it is literally half) of its population is deeply concerned with the direction in which the country is headed. The abyss between the two camps has grown in recent years, revealing a social phenomenon much more complicated than the narrative so often told in Western newspapers of a conflict between the ascendant Islamist middle class and the secular Kemalist elite.

Instead, what is happening in Turkey is that half the population solidly supports the AKP and its policies while the other half are becoming increasingly alienated from the party for a variety of reasons. This "other half" is not some unified Kemalist/secularist/nationalist opposition bloc, but rather represents a diverse array of different facets of Turkish society that have been left out of the AKP's increasingly hegemonic vision.

Of those opposed to the AKP, there are those concerned with the party's Turkish-Sunni chauvinism. These include not only members of a secular elite, but also Alevis (15 to 20 million people), Kurds (also 15 to 20 million people, though many Kurds are also Alevis), liberals (including Islamists), and leftists concerned about the AKP's neoliberal economic schemes. There are also plenty of observant Sunni Muslims who are nonetheless less pious than the AKP and/or increasingly concerned with the party's attempts to legislate its values. At the same time, there is a significant number of voters (~10%) for whom the AKP is not chauvinist enough. Most of these vote for the ultra-nationalist MHP.

The Next Steps

From Radikal

Starting with Refah in 1994, the AKP's antecedent, the AKP has gradually increased its votes since first elected office in 2002 with the one exception being the March 2009 local elections.

This is where the steps the AKP takes after the elections become crucial. Prime Minister Erdogan is determined to push through a new constitution that would institute a presidential system. Erdogan is widely thought to have designs on running for president should the changes come into being.

However, in a twist, though the AKP increased its share of the popular vote, it lost seats in parliament and is now short of the 3/5 majority it needs to unilaterally amend the constitution as it did last year. The loss of seats is a function of two factors, namely a high 10% threshold and a complicated system of closed-list proportional representation: an increase in the number of independent deputies associated with the Kurdish nationalist BDP and the increased number of voters in big cities where the party tends to do less well.

As a result of the shortfall, the AKP to some degree be pressured to compromise with opposition political parties if a new constitution is going to emerge, an objective supported by all political parties entering parliament.

That said, and despite Prime Minister Erdogan's acceptance speech yesterday in which he vowed to seek consensus as his government moves forward with a new constitution, it is possible, even likely, that the AKP will use its power to push forward its agenda with minimal compromise and consultation (as it has in the past). However, the risk, of course, is the way that power is enacted (targeting of journalists, libel suits, increased reliance on executive and administrative orders, more power to cabinet/less to parliament, limited minority rights, restrictions on association/NGO activity, etc.).

The most popular politician in the history of Turkish electoral politics, Erdogan has accomplished a tremendous electoral feat. It is more likely to encourage his appetite for power than to tame it. Power corrupts, and the more absolute the power, the more absolutely it corrupts.

Weep Not for the Opposition

And, where does the opposition stand -- and those who did not vote for the AKP? For one, it is unlikely the AKP will be able to further increase its vote. Given that the number of people unhappy with the direction in which Turkey is headed is the same number of people who did not vote for the AKP (see Pew Poll above), there is little headway the AKP can make in terms of winning additional votes -- basically, the party is maxed out.

All the same, the AKP's uncanny ability to turn nationalist then liberal -- only to do it all over again -- cannot be underestimated, and the party has a decent shot at maintaining its current numbers, especially if it decides to move again to the left so as to not be out-done by the CHP. However, I do believe the party's most recent bout of illiberalism, on full-display in its handling of the Ergenekon investigation, has burned many bridges, as did its extreme nationalist return in the past few months preceding the election.

There is little likelihood that bridges with more nationalist-inclined Kurds can be repaired given the ruling party's tenor this election cycle, especially given the failure of its Kurdish opening to deliver many concretes. Even less likely is that the party will win back the liberals and progressives who have been breaking ranks since 2005, many of whom have come to fear the party as a new authoritarian threat.

While the AKP might win some hardline nationalist votes from the MHP, it is unlikely to have much success here without losing a certain remainder of optimistic liberals who have continued to support the party for its economic successes and in spite of its illiberal tendencies.

The CHP

PHOTO from Radikal

Meanwhile, the CHP should regard its performance yesterday as a victory. "The new CHP," as the party has billed itself in the run up to the elections, managed to increase its vote share by 5% (a larger increase than the AKP) and gain 38 seats. Additionally, the CHP seems to have broadened its geographic reach, winning its party leader's home province of Tunceli while faring reasonably better in areas outside of its traditional strongholds. Support for the party might not be as deep in traditonally nationalist coastal enclaves (Antalya, Canakkale, and Izmir) as it once was, but the party has broadened its support beyond voters in these provinces while successfully moving toward establishing a different, much more liberal, pro-European electoral base.

Though no doubt disappointed, the CHP should realize it will take time for the Turkish public to trust it. A party in transition, the CHP had been up until a year ago an intolerant, oftentimes destructive force, providing people with little to no alternative but to vote for the AKP. There are likely plenty of Turkish voters who cast ballots for the AKP but are less than solid supporters; however, they do not trust the CHP either.

Further, as Milliyet columnist Asli Aydintasbas (in Turkish) writes, the CHP lacks the organizational and fundraising capacity of the AKP and should give itself some time to catch up.

All the same, CHP leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu is likely to face extreme pressure from his party. There are already rumors that the party's old guard is plotting his demise and some papers are reporting the leader offered to step down.

Message to CHP: Patience is a virtue. After many years of not being progressive, it is simply going to take time and commitment to get people to trust in the party. If the party decides to once more change course, it is likely to do more harm than good to its long-term viability.

The BDP

The BDP is the clear winner in this election. Most pre-election polls expected the BDP to win between 25 and 30 seats, a significant increase over its present 20. However, the BDP's ability to capture 36 seats has taken many by surprise, though it should not. As mentioned above, the AKP's nationalist turn (see past post) has thoroughly alienated many Kurds. Though many of these voters were already alienated, hence the BDP's electoral success in local elections in March 2009, the most recent electoral cycle has driven many to a virtual point of no return. It will be difficult for the AKP to build consensus with the party given the bad feeling and that the BDP will feel more emboldened by this recent triumph.

The good news is that two of the party's more dovish figures, Ahmet Turk and Aysel Tugluk, who were expelled from parliament in December 2009, have returned, but so has Leyla Zana, a Kurdish militant hardliner who often advocates on behalf of the PKK. Just what the BDP will do in the coming months is uncertain, but one thing is for certain: hardline Kurdish nationalism, including militancy, got a boost this election year.

The MHP

While many thought the sex scandal would finish off what was already an ultra-nationalist party in decline, the MHP managed to comfortably pass the 10% threshold with relative ease. This might in part be due to rising unrest in the southeast and Kurdish nationalism, to which equally virulent Turkish nationalism is too frequently the response. No matter how hard the AKP tries to devour this ultra-nationalist core of voters, they still do not seem comfortable voting for Erdogan. Pro-state, nationalist idealists are just simply not going to budge on this one.

Sounding the same refrain as last September's constitutional referendum, yesterday's election results reveal Turkey to be increasingly divided between those who support the ruling AKP government and those who do not.

Yesterday the AKP managed to increase its vote from the 46.58% it captured in 2007 parliamentary elections to 49.91%, though the party lost lost seats and its 3/5 majority in parliament (see yesterday's post).

Additionally, the AKP became the first party since the Democratic Party in the 1950s to win three consecutive parliamentary elections; however, unlike the Democratic Party, the AKP has become more popular each election, not less. Yet, while the results hint at the AKP's growing popularity, they also hint at a growing disconnect between the party's supporters and those who fear its burgeoning illiberal tendencies (see last Tuesday's post).

The Other Half

As echoed by the results of a recent Pew poll, Turkey is becoming an increasingly divided country. While those who support the AKP continue to enthusiastically return it to power, the other half (and it is literally half) of its population is deeply concerned with the direction in which the country is headed. The abyss between the two camps has grown in recent years, revealing a social phenomenon much more complicated than the narrative so often told in Western newspapers of a conflict between the ascendant Islamist middle class and the secular Kemalist elite.

Instead, what is happening in Turkey is that half the population solidly supports the AKP and its policies while the other half are becoming increasingly alienated from the party for a variety of reasons. This "other half" is not some unified Kemalist/secularist/nationalist opposition bloc, but rather represents a diverse array of different facets of Turkish society that have been left out of the AKP's increasingly hegemonic vision.

Of those opposed to the AKP, there are those concerned with the party's Turkish-Sunni chauvinism. These include not only members of a secular elite, but also Alevis (15 to 20 million people), Kurds (also 15 to 20 million people, though many Kurds are also Alevis), liberals (including Islamists), and leftists concerned about the AKP's neoliberal economic schemes. There are also plenty of observant Sunni Muslims who are nonetheless less pious than the AKP and/or increasingly concerned with the party's attempts to legislate its values. At the same time, there is a significant number of voters (~10%) for whom the AKP is not chauvinist enough. Most of these vote for the ultra-nationalist MHP.

The Next Steps

From Radikal

Starting with Refah in 1994, the AKP's antecedent, the AKP has gradually increased its votes since first elected office in 2002 with the one exception being the March 2009 local elections.

This is where the steps the AKP takes after the elections become crucial. Prime Minister Erdogan is determined to push through a new constitution that would institute a presidential system. Erdogan is widely thought to have designs on running for president should the changes come into being.

However, in a twist, though the AKP increased its share of the popular vote, it lost seats in parliament and is now short of the 3/5 majority it needs to unilaterally amend the constitution as it did last year. The loss of seats is a function of two factors, namely a high 10% threshold and a complicated system of closed-list proportional representation: an increase in the number of independent deputies associated with the Kurdish nationalist BDP and the increased number of voters in big cities where the party tends to do less well.

As a result of the shortfall, the AKP to some degree be pressured to compromise with opposition political parties if a new constitution is going to emerge, an objective supported by all political parties entering parliament.

That said, and despite Prime Minister Erdogan's acceptance speech yesterday in which he vowed to seek consensus as his government moves forward with a new constitution, it is possible, even likely, that the AKP will use its power to push forward its agenda with minimal compromise and consultation (as it has in the past). However, the risk, of course, is the way that power is enacted (targeting of journalists, libel suits, increased reliance on executive and administrative orders, more power to cabinet/less to parliament, limited minority rights, restrictions on association/NGO activity, etc.).

The most popular politician in the history of Turkish electoral politics, Erdogan has accomplished a tremendous electoral feat. It is more likely to encourage his appetite for power than to tame it. Power corrupts, and the more absolute the power, the more absolutely it corrupts.

Weep Not for the Opposition

And, where does the opposition stand -- and those who did not vote for the AKP? For one, it is unlikely the AKP will be able to further increase its vote. Given that the number of people unhappy with the direction in which Turkey is headed is the same number of people who did not vote for the AKP (see Pew Poll above), there is little headway the AKP can make in terms of winning additional votes -- basically, the party is maxed out.

All the same, the AKP's uncanny ability to turn nationalist then liberal -- only to do it all over again -- cannot be underestimated, and the party has a decent shot at maintaining its current numbers, especially if it decides to move again to the left so as to not be out-done by the CHP. However, I do believe the party's most recent bout of illiberalism, on full-display in its handling of the Ergenekon investigation, has burned many bridges, as did its extreme nationalist return in the past few months preceding the election.

There is little likelihood that bridges with more nationalist-inclined Kurds can be repaired given the ruling party's tenor this election cycle, especially given the failure of its Kurdish opening to deliver many concretes. Even less likely is that the party will win back the liberals and progressives who have been breaking ranks since 2005, many of whom have come to fear the party as a new authoritarian threat.

While the AKP might win some hardline nationalist votes from the MHP, it is unlikely to have much success here without losing a certain remainder of optimistic liberals who have continued to support the party for its economic successes and in spite of its illiberal tendencies.

The CHP

PHOTO from Radikal

Meanwhile, the CHP should regard its performance yesterday as a victory. "The new CHP," as the party has billed itself in the run up to the elections, managed to increase its vote share by 5% (a larger increase than the AKP) and gain 38 seats. Additionally, the CHP seems to have broadened its geographic reach, winning its party leader's home province of Tunceli while faring reasonably better in areas outside of its traditional strongholds. Support for the party might not be as deep in traditonally nationalist coastal enclaves (Antalya, Canakkale, and Izmir) as it once was, but the party has broadened its support beyond voters in these provinces while successfully moving toward establishing a different, much more liberal, pro-European electoral base.

Though no doubt disappointed, the CHP should realize it will take time for the Turkish public to trust it. A party in transition, the CHP had been up until a year ago an intolerant, oftentimes destructive force, providing people with little to no alternative but to vote for the AKP. There are likely plenty of Turkish voters who cast ballots for the AKP but are less than solid supporters; however, they do not trust the CHP either.

Further, as Milliyet columnist Asli Aydintasbas (in Turkish) writes, the CHP lacks the organizational and fundraising capacity of the AKP and should give itself some time to catch up.

All the same, CHP leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu is likely to face extreme pressure from his party. There are already rumors that the party's old guard is plotting his demise and some papers are reporting the leader offered to step down.

Message to CHP: Patience is a virtue. After many years of not being progressive, it is simply going to take time and commitment to get people to trust in the party. If the party decides to once more change course, it is likely to do more harm than good to its long-term viability.

The BDP

The BDP is the clear winner in this election. Most pre-election polls expected the BDP to win between 25 and 30 seats, a significant increase over its present 20. However, the BDP's ability to capture 36 seats has taken many by surprise, though it should not. As mentioned above, the AKP's nationalist turn (see past post) has thoroughly alienated many Kurds. Though many of these voters were already alienated, hence the BDP's electoral success in local elections in March 2009, the most recent electoral cycle has driven many to a virtual point of no return. It will be difficult for the AKP to build consensus with the party given the bad feeling and that the BDP will feel more emboldened by this recent triumph.

The good news is that two of the party's more dovish figures, Ahmet Turk and Aysel Tugluk, who were expelled from parliament in December 2009, have returned, but so has Leyla Zana, a Kurdish militant hardliner who often advocates on behalf of the PKK. Just what the BDP will do in the coming months is uncertain, but one thing is for certain: hardline Kurdish nationalism, including militancy, got a boost this election year.

The MHP

While many thought the sex scandal would finish off what was already an ultra-nationalist party in decline, the MHP managed to comfortably pass the 10% threshold with relative ease. This might in part be due to rising unrest in the southeast and Kurdish nationalism, to which equally virulent Turkish nationalism is too frequently the response. No matter how hard the AKP tries to devour this ultra-nationalist core of voters, they still do not seem comfortable voting for Erdogan. Pro-state, nationalist idealists are just simply not going to budge on this one.

Sunday, June 12, 2011

Election Night . . .

From Radikal

Election results started to come out at six o'clock in the evening Turkey time, and it became evident early on that the AKP had a commanding lead of the popular vote. However, despite capturing a near 50% of voters, the largest percentage the party has captured since it first came to power in 2002, the party fell four seats shy of the 330 seats it needs in parliament (a 3/5 majority) to push through a constitution unilaterally. For an electoral map complete with official results, click here.

This means that for the first time in a long time the AKP will have to engage in political bargaining (see yesterday's post). Last year the AKP successfully pushed through a series of constitutional amendments using its previous 3/5 majority before successfully submitting the amendments to referendum. Meanwhile, the ultra-nationalist MHP managed to comfortably surpass the 10% threshold required for political parties to enter parliament, winning 13% of the popular vote. Though the party went from 69 to 54 seats, coming in above then 10% threshold made it difficult for the AKP to meet the 3/5 marker.

The AKP's chances at gaining a 3/5 majority were further damaged by the historical success of the Kurdish nationalist party, the BDP. The BDP managed to pick up a whopping 36 seats (up from 20), no doubt a result in part to growing disenchantment with -- and, in many cases, outright hostility toward -- the party in Turkey's mostly Kurdish southeast. Running as independents so as to escape the 10% threshold, the BDP captured 6% of the vote.

The AKP's nationalist turn, presumably an effort to win voters away from the MHP, had the predictable effect of alienating Kurdish voters. Ironically, as the only other political party competitive in the region, it also contributed greatly to its failure to win 3/5 of parliamenatary seats since the BDP fared so well. AKP's efforts to defeat the MHP were a gamble, losing Kurdish votes for ultra-nationalist votes (while at the same time empowering the BDP), and the party paid the price.

In addition to MHP votes, the party did pick up a significant number of votes from the SP (Felicity Party), a legacy of Erbakan's National Outlook movement, consolidating its control over the Islamist vote. It also picked up votes from the center-right Democrat Party, which also harkens back to an earlier era. I would venture to say these are the blocs that explain the party's ability to increase its share of the popular vote.

Meanwhile, the CHP, which took enormous risks this election cycle, performed under expectations. The CHP captured 26% of the popular vote to gain 38 seats (from 97 to 135), but some expected the party to poll over 30%. During the campaign, the CHP became by far the most progressive mainline party, taking positions more pro-European, pro-peace, and pro-liberal than the AKP (again, see yesterday's post). However, the party's controversial positions, especially on the Kurdish issue, may have alienated some in its formerly nationalist base -- votes that would have gone to the AKP or the MHP. However, nonetheless, CHP leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu and ""the new CHP" managed to gain almost 3.5 million new voters and pick up seats. Whether the CHP will continue to steer Kilicdaroglu's chart or be so frustrated with the results that it changes course once more remains to be seen.

In his acceptance speech, Prime Minister Erdogan vowed to build consensus on a new constitution and reiterated that he represented all Turkish citizens, not just those who voted for him. Prime Minister Erdogans aid the consensus would be built among political parties and civil society groups, all of which would be consulted during the process. However, the prime minister made the same promise last year and fell short.

All parties support drafting of a whole new document to replace the country's 1982 constitution drafted under military tutelage, but just what will happen in the coming months is very much up in the air. The AKP is far from weak, and could well gain the 3/5 majority it needs without too much maneuvering.

UPDATE I (6/13) -- For a truly wonderful electoral map complete with candidate names according to the provinces from which they were elected, click here. The AKP won more provinces along Turkey's more secular Western coast than it has in the past, but this should not be read as a significant setback for the CHP. Though the CHP no doubt lost votes in some of these Kemalist/nationalist strongholds, including majorities, it seems to have widened its support throughout the country, picking up votes in provinces where before it was not at all competitive.

Election results started to come out at six o'clock in the evening Turkey time, and it became evident early on that the AKP had a commanding lead of the popular vote. However, despite capturing a near 50% of voters, the largest percentage the party has captured since it first came to power in 2002, the party fell four seats shy of the 330 seats it needs in parliament (a 3/5 majority) to push through a constitution unilaterally. For an electoral map complete with official results, click here.

This means that for the first time in a long time the AKP will have to engage in political bargaining (see yesterday's post). Last year the AKP successfully pushed through a series of constitutional amendments using its previous 3/5 majority before successfully submitting the amendments to referendum. Meanwhile, the ultra-nationalist MHP managed to comfortably surpass the 10% threshold required for political parties to enter parliament, winning 13% of the popular vote. Though the party went from 69 to 54 seats, coming in above then 10% threshold made it difficult for the AKP to meet the 3/5 marker.

The AKP's chances at gaining a 3/5 majority were further damaged by the historical success of the Kurdish nationalist party, the BDP. The BDP managed to pick up a whopping 36 seats (up from 20), no doubt a result in part to growing disenchantment with -- and, in many cases, outright hostility toward -- the party in Turkey's mostly Kurdish southeast. Running as independents so as to escape the 10% threshold, the BDP captured 6% of the vote.

The AKP's nationalist turn, presumably an effort to win voters away from the MHP, had the predictable effect of alienating Kurdish voters. Ironically, as the only other political party competitive in the region, it also contributed greatly to its failure to win 3/5 of parliamenatary seats since the BDP fared so well. AKP's efforts to defeat the MHP were a gamble, losing Kurdish votes for ultra-nationalist votes (while at the same time empowering the BDP), and the party paid the price.

In addition to MHP votes, the party did pick up a significant number of votes from the SP (Felicity Party), a legacy of Erbakan's National Outlook movement, consolidating its control over the Islamist vote. It also picked up votes from the center-right Democrat Party, which also harkens back to an earlier era. I would venture to say these are the blocs that explain the party's ability to increase its share of the popular vote.

Meanwhile, the CHP, which took enormous risks this election cycle, performed under expectations. The CHP captured 26% of the popular vote to gain 38 seats (from 97 to 135), but some expected the party to poll over 30%. During the campaign, the CHP became by far the most progressive mainline party, taking positions more pro-European, pro-peace, and pro-liberal than the AKP (again, see yesterday's post). However, the party's controversial positions, especially on the Kurdish issue, may have alienated some in its formerly nationalist base -- votes that would have gone to the AKP or the MHP. However, nonetheless, CHP leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu and ""the new CHP" managed to gain almost 3.5 million new voters and pick up seats. Whether the CHP will continue to steer Kilicdaroglu's chart or be so frustrated with the results that it changes course once more remains to be seen.

In his acceptance speech, Prime Minister Erdogan vowed to build consensus on a new constitution and reiterated that he represented all Turkish citizens, not just those who voted for him. Prime Minister Erdogans aid the consensus would be built among political parties and civil society groups, all of which would be consulted during the process. However, the prime minister made the same promise last year and fell short.

All parties support drafting of a whole new document to replace the country's 1982 constitution drafted under military tutelage, but just what will happen in the coming months is very much up in the air. The AKP is far from weak, and could well gain the 3/5 majority it needs without too much maneuvering.

UPDATE I (6/13) -- For a truly wonderful electoral map complete with candidate names according to the provinces from which they were elected, click here. The AKP won more provinces along Turkey's more secular Western coast than it has in the past, but this should not be read as a significant setback for the CHP. Though the CHP no doubt lost votes in some of these Kemalist/nationalist strongholds, including majorities, it seems to have widened its support throughout the country, picking up votes in provinces where before it was not at all competitive.

Saturday, June 11, 2011

What Will Happen Tomorrow (And After)?

Reuters Photo from VOA Kurdish

I gave a radio interview this morning to Voice of America's Kurdish service in which I was asked what would be the impact of tomorrow's elections on the AKP-led government's plans to introduce a new constitution. Though the interview mostly focused on the Kurdish issue, of particular interest was just how successful the AKP could be in bringing forward plans to introduce a new constitution.

If the AKP wins at least 330 seats in the parliament (it now has 336), it will be able to introduce constitutional amendments without the need for much consensus before taking them to referendum -- an approach the AKP took last year and with great success. If the party manages to surpass 367 votes, it will have a 2/3 super majority that will allow it to unilaterally overhaul the constitution without the need for referendum. While the latter is unlikely and the former in doubt, the larger issue is just how sincere the party is in its reiterations that it will seek consensus as it moves forward. At the moment, all four parties with a chance of entering parliament have pledged to adopt a new constitution.

Last year, the party showed little concern as it pushed amendments rapidly forward. Neither civil society nor opposition political parties were given much voice in the process and the result was a referendum that basically polarized the Turkish public. The Kurdish nationalist BDP boycotted the referendum while the CHP and the MHP campaigned hard against the amendments. Though the official result was 58%, the actual number of Turkish citizens who approved the changes was lower given that a large number of Kurds who did boycott.

If the referendum is taken as a measure of the support for the AKP, it can be said that roughly over one-half of Turkish citizens approve of the party and the direction in which it is taking the country. This matches more or less with what a recent Pew poll found. According to the poll, 48 percent of Turkish citizens are satisfied with the direction the country is taking; however, 49 percent responded they are dissatisfied. The satisfied voters, more or less, can be assumed to be likely to vote for the AKP, but of more interest are those who are not. How many of these voters are simply typical Turkish cynics and how many are disenchanted with the party? The rising number of potentially disenchanted is cause for concern (and that is more than an understatement).

One of the most pressing problems in Turkish politics today is the amount of polarization in Turkish political society. Some of this can be explained by the increasing illiberal attitudes and policies of the AKP (see Tuesday's post), which, of course, is made all the more problematic by the AKP's seeming lack of willingness to engage opposition parties and craft serious political compromises when it comes to making government policy. Without an entrenched rights-based liberal democracy, the lack of compromise becomes all the more disturbing. A unilaterally-drawn up constitution will only serve to further polarize the Turkish public while continuing to fail at any real resolution of the classic dilemma posed by democracy and difference.

However, should the AKP fall short of 330 seats tomorrow, the party will be more inclined to compromise. Just exactly what this process of compromise would look like and what parties it would include remains to be seen, but perhaps for the first time in a long time the AKP will be forced to work with other parties to carve out a political agenda.

At stake are Erdogan's ambitions to institute a presidential system that would facilitate his ascendancy to the presidency. If Erdogan wins comfortably tomorrow, he will be more confident in these efforts. Even should the AKP fall short of gaining 3/5 of the seats in parliament, an increase in the popular vote for the AKP will embolden the already emboldened leader to move forward in his quest.

Meanwhile, just as interestingly, the CHP, which has drastically changed its leadership and party platform, will discover whether its new position in Turkish politics will be rewarded. The CHP is expected to pick up seats and increase its vote either way, but will likely have a difficult time gaining the 30% of the vote for which the party is striving. The CHP, which has billed itself as "the new CHP," has taken enormous risks this election cycle, presenting itself as pro-Europe, pro-liberal, pro-peace, and importantly, anti-nationalist and anti-coup. With Kilicdaroglu's victory over the party stalwart and former party secretary-general Onder Sav last year, the party has turned 180-degrees in many of its policies, especially in regard to the Kurds and its former pro-military/pro-coup attitude. Defeating Sav, Kilicdaroglu remarked, "The empire of fear is over in the CHP. Now it is time to end the empire of fear in Turkey."

The MHP will also face a serious test tomorrow. A little less than a month ago, there was serious question as to whether the ultra-nationalist party would be able to surpass the 10% threshold required to enter parliament. However, polls conducted at the end of June put the party safely over the threshold. That said, just how well the party does tomorrow will have an impact on the number of seats allocated to the AKP and CHP. The AKP has been competing for its nationalist voter base while the CHP's recent positions, especially in regard to the Kurds, might have alienated some in its former nationalist base to vote for the MHP.

And, finally, not without its own test will be the Kurdish nationalist BDP. The BDP currently has 20 seats in parliament, just enough to form a parliamentary group and be represented. However, there is little doubt that the BDP will surpass this number and could pick up well over 30 seats. Though the BDP candidates are running as independents since there in no chance they could meet the 10 percent threshold, the rising force of the party in the southeast and in Western cities populated by a large number of Kurdish migrants will indubitably be one of the most important stories of this election cycle. As its main challenger, the AKP's increased nationalist rhetoric is likely to work in favor of the party.

We'll see what tomorrow brings.

I gave a radio interview this morning to Voice of America's Kurdish service in which I was asked what would be the impact of tomorrow's elections on the AKP-led government's plans to introduce a new constitution. Though the interview mostly focused on the Kurdish issue, of particular interest was just how successful the AKP could be in bringing forward plans to introduce a new constitution.

If the AKP wins at least 330 seats in the parliament (it now has 336), it will be able to introduce constitutional amendments without the need for much consensus before taking them to referendum -- an approach the AKP took last year and with great success. If the party manages to surpass 367 votes, it will have a 2/3 super majority that will allow it to unilaterally overhaul the constitution without the need for referendum. While the latter is unlikely and the former in doubt, the larger issue is just how sincere the party is in its reiterations that it will seek consensus as it moves forward. At the moment, all four parties with a chance of entering parliament have pledged to adopt a new constitution.

Last year, the party showed little concern as it pushed amendments rapidly forward. Neither civil society nor opposition political parties were given much voice in the process and the result was a referendum that basically polarized the Turkish public. The Kurdish nationalist BDP boycotted the referendum while the CHP and the MHP campaigned hard against the amendments. Though the official result was 58%, the actual number of Turkish citizens who approved the changes was lower given that a large number of Kurds who did boycott.

If the referendum is taken as a measure of the support for the AKP, it can be said that roughly over one-half of Turkish citizens approve of the party and the direction in which it is taking the country. This matches more or less with what a recent Pew poll found. According to the poll, 48 percent of Turkish citizens are satisfied with the direction the country is taking; however, 49 percent responded they are dissatisfied. The satisfied voters, more or less, can be assumed to be likely to vote for the AKP, but of more interest are those who are not. How many of these voters are simply typical Turkish cynics and how many are disenchanted with the party? The rising number of potentially disenchanted is cause for concern (and that is more than an understatement).

One of the most pressing problems in Turkish politics today is the amount of polarization in Turkish political society. Some of this can be explained by the increasing illiberal attitudes and policies of the AKP (see Tuesday's post), which, of course, is made all the more problematic by the AKP's seeming lack of willingness to engage opposition parties and craft serious political compromises when it comes to making government policy. Without an entrenched rights-based liberal democracy, the lack of compromise becomes all the more disturbing. A unilaterally-drawn up constitution will only serve to further polarize the Turkish public while continuing to fail at any real resolution of the classic dilemma posed by democracy and difference.

However, should the AKP fall short of 330 seats tomorrow, the party will be more inclined to compromise. Just exactly what this process of compromise would look like and what parties it would include remains to be seen, but perhaps for the first time in a long time the AKP will be forced to work with other parties to carve out a political agenda.

At stake are Erdogan's ambitions to institute a presidential system that would facilitate his ascendancy to the presidency. If Erdogan wins comfortably tomorrow, he will be more confident in these efforts. Even should the AKP fall short of gaining 3/5 of the seats in parliament, an increase in the popular vote for the AKP will embolden the already emboldened leader to move forward in his quest.

Meanwhile, just as interestingly, the CHP, which has drastically changed its leadership and party platform, will discover whether its new position in Turkish politics will be rewarded. The CHP is expected to pick up seats and increase its vote either way, but will likely have a difficult time gaining the 30% of the vote for which the party is striving. The CHP, which has billed itself as "the new CHP," has taken enormous risks this election cycle, presenting itself as pro-Europe, pro-liberal, pro-peace, and importantly, anti-nationalist and anti-coup. With Kilicdaroglu's victory over the party stalwart and former party secretary-general Onder Sav last year, the party has turned 180-degrees in many of its policies, especially in regard to the Kurds and its former pro-military/pro-coup attitude. Defeating Sav, Kilicdaroglu remarked, "The empire of fear is over in the CHP. Now it is time to end the empire of fear in Turkey."

The MHP will also face a serious test tomorrow. A little less than a month ago, there was serious question as to whether the ultra-nationalist party would be able to surpass the 10% threshold required to enter parliament. However, polls conducted at the end of June put the party safely over the threshold. That said, just how well the party does tomorrow will have an impact on the number of seats allocated to the AKP and CHP. The AKP has been competing for its nationalist voter base while the CHP's recent positions, especially in regard to the Kurds, might have alienated some in its former nationalist base to vote for the MHP.

And, finally, not without its own test will be the Kurdish nationalist BDP. The BDP currently has 20 seats in parliament, just enough to form a parliamentary group and be represented. However, there is little doubt that the BDP will surpass this number and could pick up well over 30 seats. Though the BDP candidates are running as independents since there in no chance they could meet the 10 percent threshold, the rising force of the party in the southeast and in Western cities populated by a large number of Kurdish migrants will indubitably be one of the most important stories of this election cycle. As its main challenger, the AKP's increased nationalist rhetoric is likely to work in favor of the party.

We'll see what tomorrow brings.

Friday, June 10, 2011

Getting the Nationalist Vote . . .

EPA Photo from Al-Jazeera English

As the part of the AKP's continuing efforts to cater its election rhetoric to nationalist voters, Prime Minister Erdogan has declared that he would have executed jailed PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan had he been prime minister at the time. Erdogan accused the MHP of giving its support to a 2002 that abolished the death penalty, implying that problems with Ocalan would have been solved if the government at the time had properly sent him to the gallows.

The remarks came in response to unfounded allegations from the MHP that the AKP-led government was in negotiations with the PKK to arrange for Ocalan's release. At the moment, the AKP and the ultra-nationalist MHP are both competing to win nationalist votes. For more on this dynamic, click here.

While the AKP might succeed in luring votes away from MHP by taking a hardline position on the Kurdish issue, it does so at the cost of further alienating Kurdish voters in Turkey's mostly Kurdish southeast. Recently, the party has been behaving as if these voters simply do not matter and the result will indubitably be a historic increase in the number of votes the Kurdish nationalist party receives on Sunday.

More troubling is that the AKP's election rhetoric will seriously hamper its chances of repairing its relationship with nationalist Kurds with whom it will likely have to work with to some degree if it is going to pass a constitution that takes all views into account, as Erdogan has expressed is his intention. Given the party's nationalist turn, it will be very difficult to win Kurdish nationalist voters, even those who are not necessarily supportive of the PKK-affiliated BDP.

Meanwhile, an even bigger danger lurks that could further compounds AKP's Kurdish problem. Ocalan, through his lawyers, is threatening a drastic increase in PKK violence should the government not move to negotiate with the PKK by June 15. The specter of renewed PKK violence of the kind last summer will only serve to distract from the government's efforts to pass a constitution and further polarize Turks and Kurds.

As the part of the AKP's continuing efforts to cater its election rhetoric to nationalist voters, Prime Minister Erdogan has declared that he would have executed jailed PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan had he been prime minister at the time. Erdogan accused the MHP of giving its support to a 2002 that abolished the death penalty, implying that problems with Ocalan would have been solved if the government at the time had properly sent him to the gallows.

The remarks came in response to unfounded allegations from the MHP that the AKP-led government was in negotiations with the PKK to arrange for Ocalan's release. At the moment, the AKP and the ultra-nationalist MHP are both competing to win nationalist votes. For more on this dynamic, click here.

While the AKP might succeed in luring votes away from MHP by taking a hardline position on the Kurdish issue, it does so at the cost of further alienating Kurdish voters in Turkey's mostly Kurdish southeast. Recently, the party has been behaving as if these voters simply do not matter and the result will indubitably be a historic increase in the number of votes the Kurdish nationalist party receives on Sunday.

More troubling is that the AKP's election rhetoric will seriously hamper its chances of repairing its relationship with nationalist Kurds with whom it will likely have to work with to some degree if it is going to pass a constitution that takes all views into account, as Erdogan has expressed is his intention. Given the party's nationalist turn, it will be very difficult to win Kurdish nationalist voters, even those who are not necessarily supportive of the PKK-affiliated BDP.

Meanwhile, an even bigger danger lurks that could further compounds AKP's Kurdish problem. Ocalan, through his lawyers, is threatening a drastic increase in PKK violence should the government not move to negotiate with the PKK by June 15. The specter of renewed PKK violence of the kind last summer will only serve to distract from the government's efforts to pass a constitution and further polarize Turks and Kurds.

Monday, June 6, 2011

Even MHP Recognizes the Kurdish Problem

PHOTO from Radikal

Even the ultra-nationalist MHP seems to recognize the Kurdish problem. In the party's first campaign rally in the mostly Kurdish city of Diyarbakir yesterday, MHP leader Devlet Bahceli went a step ahead of Erdogan in recognizing the persistence of the Kurdish problem (for story, in Turkish, click here).

In Diyarbakir last Wednesday, Prime Minister Erdogan declared the Kurdish problem "solved," seemingly closing the peace initiative his government announced in July 2009. In contrast, Bahceli said, "I know you have a problem, but the solution is not street protests." Bahceli, like Erdogan, called for more economic development in the region while arguing that amending the constitution to end prohibitions on education in mother tongue, a long-time and principal demand of many Kurds, will not "fill your stomach."

In the past, the MHP has taken the most hawkish position on the Kurdish issue. An ultra-nationalist Turkey party with historical roots to gangs that target leftists and nationalist Kurds, the party has little hope of being competitive in the region. At the same time, it is significant that even it felt the need to hold a campaign rally in Diyarbakir.

In his speech, Bahceli said Kurds are regarded as equal to Turks, stressing that they too are members of the Turkish "nation," a claim many more nationalist Kurds adamantly reject. While many Kurds are fine being Turkish citizens, the claim that they are Turks due to their bonds of citizenship with the Turkish state (a claim stipulated in Article 66 of the Turkish constitution) raises the ire of more than a small number.

The CHP has proposed amending the constitution to eliminate the controversial article so that Turkish citizenship will not longer beat an ethnic definition, a move which has been denounced by both the AKP and the MHP. It was the first mainline Turkish party in the history of the Turkish republic to do so.

Even the ultra-nationalist MHP seems to recognize the Kurdish problem. In the party's first campaign rally in the mostly Kurdish city of Diyarbakir yesterday, MHP leader Devlet Bahceli went a step ahead of Erdogan in recognizing the persistence of the Kurdish problem (for story, in Turkish, click here).

In Diyarbakir last Wednesday, Prime Minister Erdogan declared the Kurdish problem "solved," seemingly closing the peace initiative his government announced in July 2009. In contrast, Bahceli said, "I know you have a problem, but the solution is not street protests." Bahceli, like Erdogan, called for more economic development in the region while arguing that amending the constitution to end prohibitions on education in mother tongue, a long-time and principal demand of many Kurds, will not "fill your stomach."

In the past, the MHP has taken the most hawkish position on the Kurdish issue. An ultra-nationalist Turkey party with historical roots to gangs that target leftists and nationalist Kurds, the party has little hope of being competitive in the region. At the same time, it is significant that even it felt the need to hold a campaign rally in Diyarbakir.

In his speech, Bahceli said Kurds are regarded as equal to Turks, stressing that they too are members of the Turkish "nation," a claim many more nationalist Kurds adamantly reject. While many Kurds are fine being Turkish citizens, the claim that they are Turks due to their bonds of citizenship with the Turkish state (a claim stipulated in Article 66 of the Turkish constitution) raises the ire of more than a small number.

The CHP has proposed amending the constitution to eliminate the controversial article so that Turkish citizenship will not longer beat an ethnic definition, a move which has been denounced by both the AKP and the MHP. It was the first mainline Turkish party in the history of the Turkish republic to do so.

Tuesday, May 31, 2011

Grey Wolf Attacks on BDP Politicians

Ultra-nationalist youth attacked two people distributing waivers for Labor, Democracy, and Freedom Block candidate Emrullah Bingul in Izmit, a town just outside Istanbul (and where I spent my first year in Turkey). The attackers were reported to be Grey Wolves, a fascist youth organization connected to the ultra-nationalist MHP. The attack took place at a mosque near the main municipal building where supporters of the BDP and the Labor Party (EMEP) were distributing campaign material.

The previous day, the convoy of candidate Levent Tuzel, a member of the same party block, was attacked in Istanbul, also reportedly by Grey Wolves.

The Grey Wolves have a nasty past. Linked to numerous attacks on leftists since the 1970s, including assassinations and wholesale massacres of Turks who deviate from their Turkish-Sunni chauvinist idealism, the youth groups are still around and attack vulnerable targets when tensions are high.

In the wake of a massive sex scandal, the MHP is still hovering at around 10% in public opinion polls, the threshold parties must meet in order to enter parliament. If the the MHP falls under this threshold, ultra-nationalism, a force in Turkey that has been on the decline in recent years (though there were huge outbursts in 2007) will no longer be represented in parliament. However, there is legitimate fear that the party, which has renounced violence, might become more reactionary should this come to fruition.

For a bit more about the ultra-nationalist right, see this early post from 2008. An excerpt:

The previous day, the convoy of candidate Levent Tuzel, a member of the same party block, was attacked in Istanbul, also reportedly by Grey Wolves.

The Grey Wolves have a nasty past. Linked to numerous attacks on leftists since the 1970s, including assassinations and wholesale massacres of Turks who deviate from their Turkish-Sunni chauvinist idealism, the youth groups are still around and attack vulnerable targets when tensions are high.

In the wake of a massive sex scandal, the MHP is still hovering at around 10% in public opinion polls, the threshold parties must meet in order to enter parliament. If the the MHP falls under this threshold, ultra-nationalism, a force in Turkey that has been on the decline in recent years (though there were huge outbursts in 2007) will no longer be represented in parliament. However, there is legitimate fear that the party, which has renounced violence, might become more reactionary should this come to fruition.

For a bit more about the ultra-nationalist right, see this early post from 2008. An excerpt:

Although the early [MHP] was not particularly successful in electoral politics, it gained notoriety when it founded its youth organization, the Hearths of the Ideal (Ülkü Ocakları). Members of the group began to call themselves the "Grey Wolves" ("Bozkurtlar") and the group soon took on a paramilitary dimension when it opened camps to train members to engage in violent acts against the Turkish left. The enemy of the time was not Islamist, but communist, and the Grey Wolves became an increasing threat to those who it saw as opposed to their Sunni Muslim-Turkish identity. By the late 1970s, political violence against the left was rife and reveals itself most violently in the slaughter of Alevis that took place in Kahramanmaraş in December 1978 when well over 100 Alevis were murdered in a pogrom organized by the Grey Wolves. The Grey Wolves had two reasons to hate the Alevis: first, they practice a heterodox form of Shi'a Islam that was at odds with their Sunni bigotry, and second, the Alevis were generally aligned with the left. It is also likely that the group was responsible for the May Day violence of 1977 in which 39 people lost their lives when unknown gunmen opened fire on leftist protesters and operated with the cooperation of some sectors of the Turkish Armed Forces as part of the theorized "deep state" (see Jan. 25 post).Given that MHP's meeting the 10% threshold is the big question for the upcoming June 12 elections, I thought it might be useful to link back to this so readers can get more of a sense of the party's origins and just where it stands in the Turkish political landscape.